A LITTLE NOTE BEFORE YOU GO INTO THE FASCINATING STORIES OF TROUBLED WRITERS THAT CROSSED THE TROUBLED WATERS OF IRELAND (WHETHER COMING OR GOING)…..

Here in this blog, there are things revealed that nobody has seen or read before. Even I didn’t know about White and my grandfather, ‘til I rummaged around in the attic…. ALL MY WORK IS FREE. ISN’T THAT SOMETHING! I DON’T WANT TO CHARGE PEOPLE, PUSH THEM INTO A CORNER TO SUBSCRIBE IN A PAID FASHION in this age of INFLATION! SO IT IS ALL FOR FREE! BUT IF YOU FEEL LIKE BUYING ME A COFFEE, SOMEBODY FINALLY TAUGHT ME HOW TO INSTALL THE BUTTON…

We mostly think of writers and artists leaving this island because of its parochial, knobbly-kneed culture, its squinting windows, its drunken-ess, its moral hegemony, its brutal cruelty (by oppressors) and its myopia…you know, the list goes on and on. James Joyce and Samuel Beckett fled, and many others fled the dark, wet island. I’ve tried many times to flee, living in Poland for many years, and India and even, in desperation, America. But I always came back like a boomerang. I’m still dreaming of lemons and olives and warm seas, that one day I’ll wake up to that, but for now it’s here, the humdrum of the banana Republic, and all its madness and all its beauty.

Joyce fled to Trieste with Nora Barnacle and taught English in the very early 20th Century. He lived there for over a decade, completing Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist and beginning the tome of Ulysses there.

He taught English at the Berlitz School until in March 1905 foreigners were expelled on suspicion of espionage but Joyce returned to Trieste to teach at the school again.

Joyce’s sisters Eileen and Eva visited him and Nora in Trieste. Eileen fell in love with František Schaurek, (from Bohemia/ Czechoslovakia) who had come to study English with James. In 1909 Joyce came back to Ireland with Nora and the children to start the new Volta cinema in Dublin. Eileen, his sister, played the piano in the cinema hall. Bożena Berta Delimata, daughter of Eileen and František, saw her Uncle James and Aunt Nora fighting about Nora not taking Joyce’s work seriously enough, and Bożena saw him burn a manuscript in the open fire. 500 pages were burned in the stove before Eileen saved the remaining pages, burning her hands. Joyce bought her a new coat as a gesture of thanks. Bożena Berta was named after Joyce’s characters in the play Exiles, which Joyce completed during World War One. After Bożena’s birth, her mother was pregnant again and fell out of a tram in Dublin.

Bożena Berta (‘Bonzo’) ended up marrying a Polish chap called Tadeusz Delimata, from Lvov (then Poland, now Ukraine) whose uncle had been riddled with bullets in the Katyn forests, hunted by Papa Stalin. Tadek and Bożena somehow ended up in Bray, Co. Wicklow in the 1950’s and opened a clock repair shop, where some opticians or dental spooks now operate, but from the 1970s their clock shop, Delimata, served as the salvager of time in the town of Bray. Once, my friend’s father brought in a manual camera to be fixed, as Tadeusz also fixed such things as well, and was handed back, many weeks later, a box of bits and pieces, the sad carcass of a camera that would never again see light. He was however brilliant at fixing clocks. And others remember Delimata repairing cameras perfectly.

There were some random ‘refugees’ during the war years in Ireland, though De Valera tried to keep them out. Tadeusz met an Austrian Jewess in Bray, called Anneliese Fuchs (Hogan, married name) who was actually a ‘mischling of 1st degree’ meaning that her parent had been a converted Jew (simply for the Third Reich to note they were non-Aryan, hence fleeing to Ireland ) lived in Glencree, Co. Wicklow and they discovered that they had been born in the same hospital in Lvov on the same day.

Exiles

We know all about writers like Joyce and Beckett who went into self imposed exile, but we hear less about those who ended up in Ireland, in search of something or in their own kind of exile. Let’s start with Antonin Artaud, the extraordinary French playwright and inventer of the Theatre of Cruelty, who, some say, had his own pet lobster that he walked around Paris on a lead.

Antonin Artaud arrived in Ireland in 1937 with what he claimed to be St Patrick’s staff. To him, this was a spiritual mission of sorts, and the staff possessed magical qualities. Along with the staff, he carried a letter of introduction from the Irish Legation in Paris, who were unaware of the nature of his pilgrimage. He would end up in Mountjoy Prison for his troubles, before being deported as a “destitute and undesirable alien.”

And then, there was Gerard Manly Hopkins, whose poetry I have never liked. All that assonance and alliteration makes my stomach turn. But it wasn’t always nor for eternity that he wrote the likes of The Windover, that blustery poem that was in the ‘Soundings’ Anthology of poetry for the Leaving Certificate. Ireland put a stop to that.

I caught this morning morning's minion, king-

dom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

from the Windover, by Gerard Manly Hopkins

His darkest years were spent in Ireland. He detested the Society of Jesus dominated UCD where he wasn’t very popular as Professor of Classics, being an English Catholic convert, in 1885. He was a bit too sensitve to deal with some of the back biting. Of the 28 poems he wrote in Ireland, the six known as the Terrible Sonnets reflect his bleak depression. The eldest child of a London shipping insurer, he had converted to Catholicism after leaving Oxford and became Jesuit priest. He privately wrote poetry that used a radical system of metrics that nobody seemed to appreciate. A poem written in north Wales was inspired by a shipwreck in the North Sea whose victims included five German nuns. The Wreck of the Deutschland baffled its readers and his poetic career came to nothing.

But the post in UCD was to change all of that, the hope that his sense of failure would dissipate. He was still writing when he reached Ireland, but his sense of failure was intense and his mood was not helped by his disappointment in finding how far Dublin had fallen from its Georgian elegance of the previous century. The play by The Stomach Box Theatre Company (2009) “No Worst, there is None’ was a macabre production about Hopkins living and working in Newman House, and where he had plunged into an abyss of depression and the title of the play “No Worst, there is None’ is the title of one of his Terrible Sonnets (no. 49). These sonnets are full of existential terror, and are far better than his bright, impressionist nature poems that use that awful metric.

“cliffs of fall . . . frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed” - from Sonnet no. 49, of The Terrible Sonnets, by Gerard Manly Hopkins, who died of depression and typhoid in Dublin

“Hopkins died of typhoid, basically from bad sanitation,” says Tighe of the Theatre Company “Either the Jesuits didn’t have the money to spend at that time, or they wouldn’t invest it in modernising the facilities.”

Tolkien himself lived in Ireland, teaching English Literature in Queen’s University and he didn’t seem to like it either. “Professor Sayer: I’ve gone for one or two walks with Tolkien, and he did talk to me about natural scenes he visited. One of the things I noticed, which surprised me from the start, was the way in which he regarded certain natural scenes as evil. This came up most strongly after he’d been examining in order — that is to say classifying students in an Irish University according to their achievements in the English language and literature. He described Ireland as a country naturally evil. He said he could feel evil coming from the earth, from the peat bogs, from the clumps of trees, even from the cliffs, and this evil was only held in check by the great devotion of the southern Irish to their religion. This was a very strange view, and was not one I could even have guessed.

Carpenter: I have nothing to add to that extremely illuminating reminiscence except that, to say that he was a very knowledgeable observer of the details of scenery…”

I think that Tolkien’s expereinces and perceptions of Ireland would merit a whole blog of their own. I haven’t even mentioned Dylan Thomas and his sojourn in a remote cottage in Ardara, Co. Donegal in the summer of 1935 which sent him into a dark depression and great bouts of drinking…

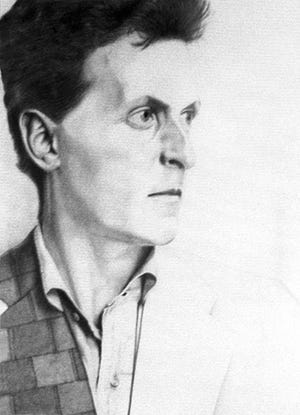

There was also Wittgenstein, who was professor of Philosphy in Cambridge and who came to Ireland to stay in a cottage in Rosroe, Co Galway, from November 1947 to June 1949, among a settlement of six houses set between the mouth of Killary Harbour and a sea inlet called ‘Little Killary’. ‘Quay House’, on the village pier, was owned by Myles Drury (1904–87), elder brother of a former Wittgenstein student, Maurice O’Connor Drury (1907–76). Familiarly called ‘Con’, Maurice was a psychiatrist employed by St Patrick’s Hospital, James’s Street, Dublin. This would later prove to be a strange coincidence when he ended up in that hospital, himself.

Locals regarded Wittgenstein as eccentric, probably because he was quite rude and didn’t attempt to integrate into the community. He did interact with the birds, however, as he made sure to feed them daily. The Philosopher and the Birds’ (1953) a poem by Richard Murphy reveals how after Wittgenstein’s departure to visit friends and family, ‘hordes of village cats … massacred his birds’. He fell into a deep depression in 1948, ending up under the hatchet of the same psychiatrist, Dr. Norman Moore, as my grandmother did, around the same time in St. Patrick’s hospital, James Street, Dublin. He’d been living in of all places, Red Cross, Co. Wicklow, as a guest of a farming family, the Kingstons, at Kilpatrick House. Dr Norman Moore suggested the cottage in Galway would be a remedy.

T.H.White. One of my favourite writers….

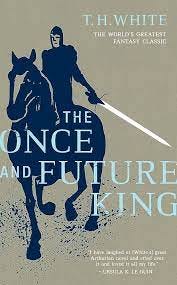

White came to Ireland in 1939 to escape the war. He went from Belmullet Co Mayo to Trim Co Meath for five years and wrote The Sword in the Stone there which was instantly successful. He told Seán Glynn; “You know Seán, I’ll never make it as a poet. I know all about poetry, its history, its tecniques, its forms. But your man Yeats had more poetry in his little finger than I have in my whole body.’ (Interview with Donal O’Donovan, 1992). He was a great friend of my grandfather, who was a sort of anchor for him during his years in Ireland. He frequently stayed with my grandparents in Dunlaoire, Co. Dublin. Unlike my grandfather, White was aware of 20th century Anglo-Irish relations. He was interested in Irish folklore, myth and history. He even learned some Irish. He said endearing things about families who he stayed with in Ireland but he would then cut through with condemning the Irish as ‘drunks who can't run a country without murdering each other.’

Through little parables in The Sword and the Stone, he has Wart (the young King Arthur), during his rights of passage with Merlyn, turning into various animals and in the course of this he manages slamming imperialism almost in the same breath as he rants about the Welsh, Scots and Irish. Take what Merlyn says:

Also I would like to point out that the Norman Conquest was a process of welding small units into bigger ones—while the present revolt of the Gaelic Confederation is a process of disintegration. They want to smash up what we may call the United Kingdom into a lot of piffling little kingdoms of their own. That is why their reason is not what you might call a good one." He scratched his chin again, and became wrathful. "I never could stomach these nationalists," he exclaimed. "The destiny of Man is to unite, not to divide. If you keep on dividing you end up as a collection of monkeys throwing nuts at each other out of separate trees.

It is the beligerent attitude of the conqueror, undisguised. Arthur tries to extinguish violence against what he paints as a very otherised and monstrous bunch of Picts and Irish. He seems to intrude in to the text and hijack Arthur to convey his own feelings about British imperialism and Irish Nationalism. Ireland was, at the time he lived here, crawling out of the 800 year grip on the island by the English. It was still the Irish Free State, not the Republic. Well, it was by 1937. He makes a direct parallel between Mordred's personal army, his proto-Irish nationalist 'Thrashers', and Nazis!

Mordred had begun dressing with this dramatic simplicity since the time when he had become a leader of the popular party. Their aims were some kind of nationalism, with Gaelic autonomy, and a massacre of the Jews as well, in revenge for a mythical saint called Hugh of Lincoln. There were already thousands, spread over the country, who carried his badge of a scarlet fist clenching a whip, and who called themselves Thrashers.

This may have been due to Ireland’s neutrality, which did involve some shenanigans with Nazi spies. Remember though that White was in Ireland to avoid conscription. Merlyn says:

England's difficulty, we used to say, is Ireland's opportunity. This is their chance to pay off racial scores, and to have some blood-letting as sport, and to make a bit of money in ransoms.

White was very aware of ‘The Irish question'. It’s strange for me to find all of this out, since at that very time my paternal grandfather, who lived down the road from my mother’s parents, was interned in the Curragh camp, Co. Kildare for enacting that very principle England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity by inviting Nazi spies to parachute into Ireland to collaborate with the IRA, with that end in view.

White indulged in English stereotypes about the Irish: 'The great Gaels of Ireland are the men that God made mad, For all their wars are merry, and all their songs are sad'". He draws a distinction ( through Merlyn) between the IRA-style approach of the Thrashers and the milder (still loathsome) Scottish nationalists.

Yet, he seemed happy enough in Ireland. My mother remembered White in their house in Dunlaoire, Co. Dublin and that he was quite close to my uncle Norman, to whom he taught falconry, which White was obsessed with. He had hawks while he stayed here, as it was a sport that seemed to keep him sane.

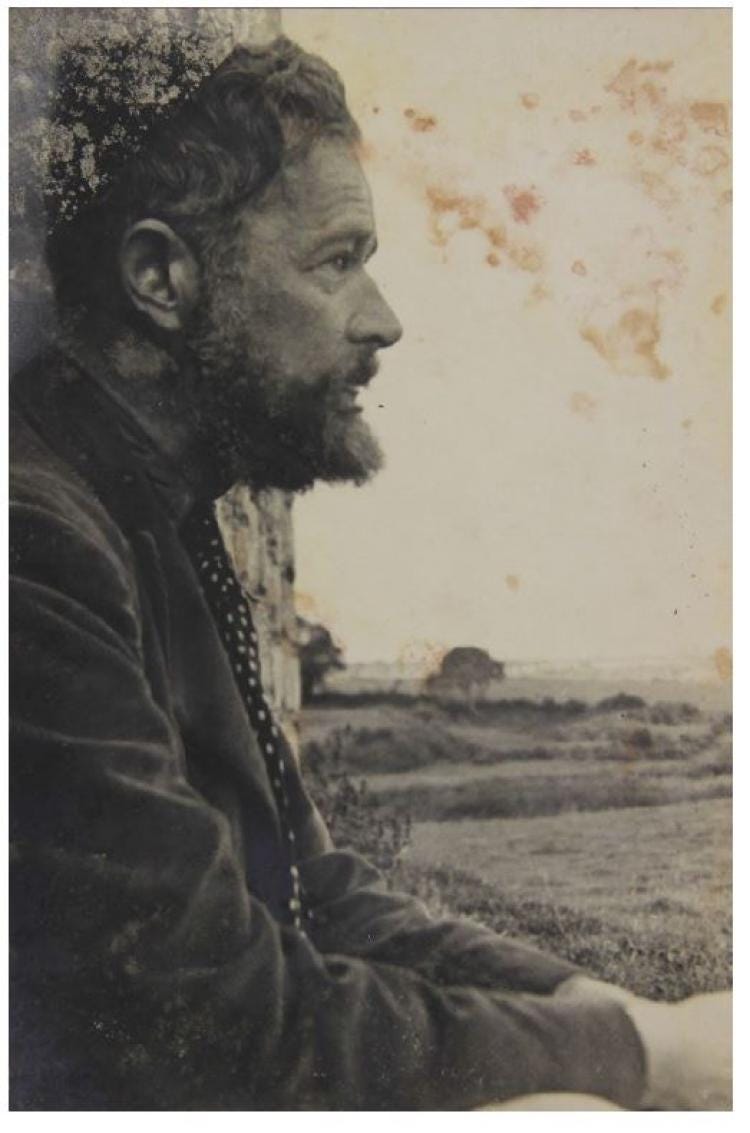

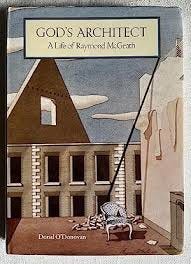

‘The real Terence Hanbury White was tall, bearded, seeply self aware, complex, unhappy much of the time, eventually alchoholic and avowedly homosexual (Donal O’Donovan, God’s Architect, p. 105)

My grandfather viewed White as a man of ‘tremendous imagination and humour which enlivened every encounter with him. When he came to Dublin he sometimes stayed with us and on one occasion he gave my son [Norman] a kestrel, made a hood and jesses for it and taught him the elements of falconry’ White believed what Merlyn said in The Sword and the Stone’: ‘The best things for being sad is to learn something.’ White had taken to falconry in Stowe and was a relentless fisher of salmon and shooter of wild geese- all in the tradition of Anglo Irish landlords. “He did not hide it from himself- he killed these creatures because he loved them.’ (said Walter Allen of White)

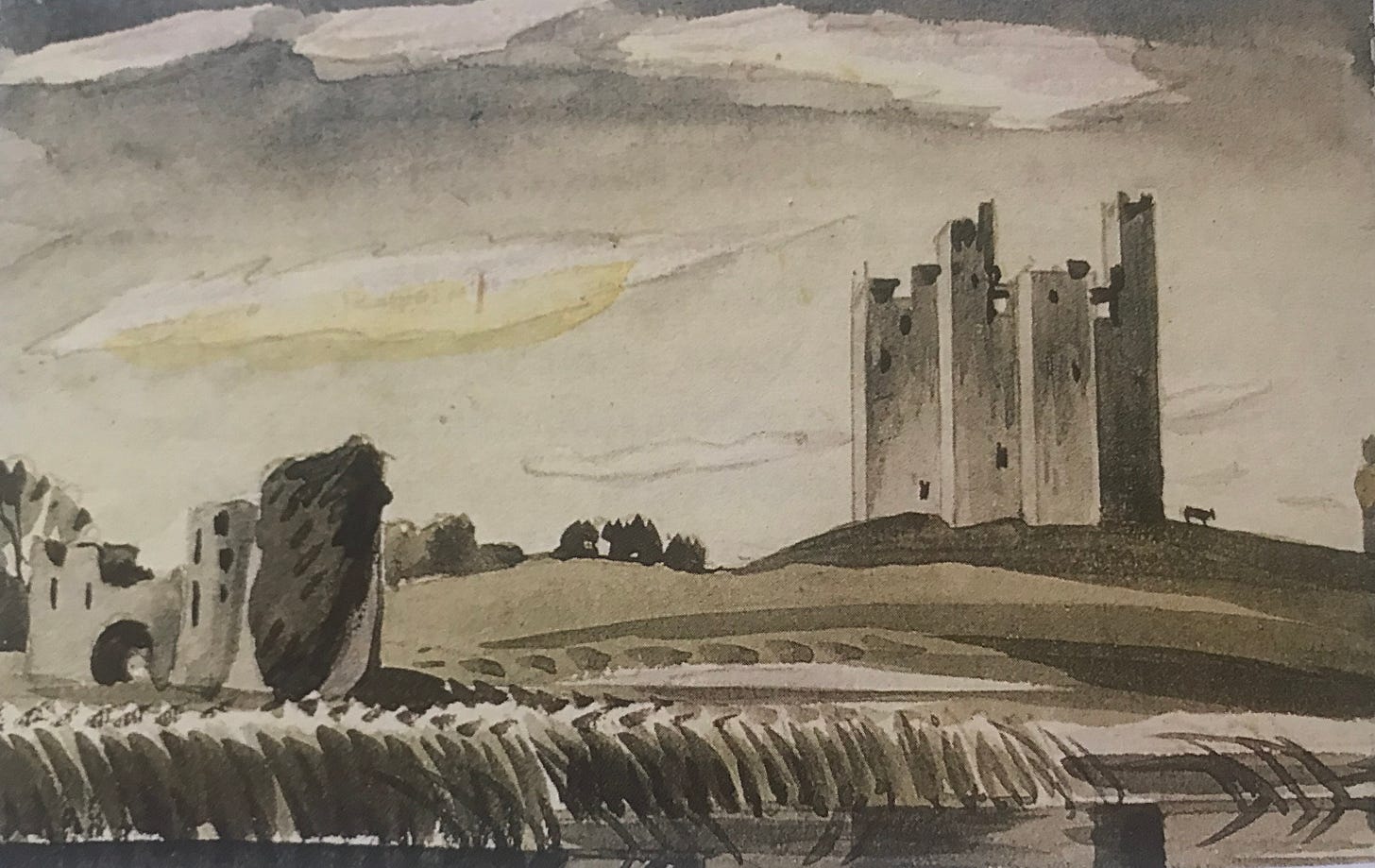

Maybe White liked my my grandfather becasue he was a shy, retiring architect from Sydney. He’d come over to Cambridge on the Osterly ship in 1926 to Cambridge, and the war brought him to Ireland. He may have felt as displaced here as White, despite that only two generations back my grandfather’s paternal ancestor John McGrath came from Bagnesltown Co. Carlow, from which he’d possibly fled a workhouse after the famine, married Edith Sorrel in England and became a ship’s doctor on a ship that took them to New Zealand, and later, Sydney. Maybe my grandfather didn’t like the Irish, nor Ireland himself ( his paintings show that he loved the landscape at least, but sure the English loved that too).

Maybe the (subconcsious, ancestral) memories were painful for my grandfather, and that although Ireland was a refuge from the War, he’d had to abandon his pretty impressive vocation as a modernist architect in London and Cambridge, and work for the Office of Public Works here, as Chief Architect. He’d become pretty well known as a co-architect of the BBC buildings in London and the Victorian house ‘Finella’ in Cambridge that he completely redesigned and lived in with Manny Forbes. Finella was a Pictish goddess that my grandfather had dreamed about. She was the goddess of glass, who smashed at the foot of a waterfall…

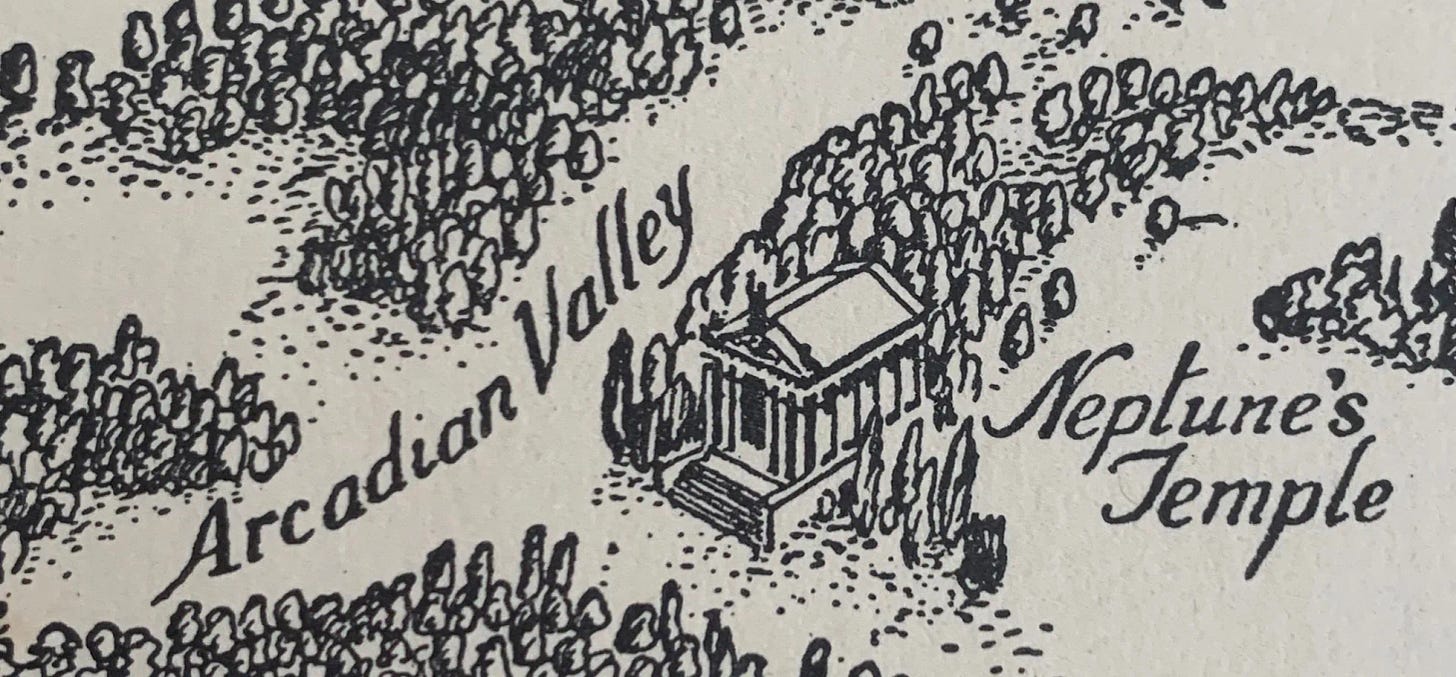

White returned to children’s literature with Mistress Masham’s Repose (1946) and The Master (1957) post-war age. The map in Mistress Masham’s Repose was drawn by my grandfather who was not just an architect but an illustrator, watercolorist, printmaker and interior designer, who had arrived in London in the 1920s. In 1940 when my grandparents, mother and uncle moved to Ireland in a Ford Model T, White had already arrived here in 1939- so who knows, he might have beckoned my war-torn grandparents over to the island. McGrath was paid $50 by the American publishing house, G.P. Putnam & Sons, for the map of Malplaquet, apparently a ‘top fee for a map of this sort’.

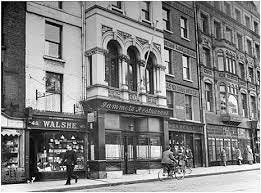

He, though far less than poor old Gerard Manly Hopkins, flirted with Catholicism and gave my mother Jenny a shiny little box of rosary beads. His two red setters, my mother recalled ‘were called Killie and Slop Slop. When Brownie, his bitch died he sat up with the corpse for two whole days and took the bus to Dubin and got as drunk as possible for nine whole days.’ He loved O’Mara’s on Aston Quay and the United Arts Club and he ate out at Jammet’s, frequently with my grandparents.

So it seems that, like many Englishmen, White detested Ireland, despite the refuge it had given him in the war years and his copious creativity and success while on the island. Unlike the other writers I mention above, he did not spiral into the abyss of depression that others have, here. White liked, and felt familiar with my grandfather because of the Cambridge connection. And my grandfather liked him. He told Sylvia Townsend Warner, White’s biographer in 1968 (White was dead by then), “I was absurdly jealous of his charm and good looks because he invited a young American girl to tea in his rooms and inscribed a copy of ‘Loved Helen’ to her. She subsetquenlty became my wife.’ That is, my grandmother Mary Catherine Crozier from Dallas, Texas who had come to study French and Spanish at Cambridge in 1929.

My grandfather was annoyed with Sylvia T-W, when the biography of White came out, for her emphasis on the drinking and homosexuality, to which she responded: “it was on White’s own witness that I included the drinking and homosexuality. He made little of them to others but did not blink them, nor his underlying melancholy, to himself.… I wish that my letter to you asking if I could see [White’s letters] had reached you. But obviously it did not, for I am sure you would not have left it unanswered.” But- shockingly- the letter had reached my grandfather! She’d asked for my grandafther’s memories of the Cambridge years and he had ignored the letter for some strange reason? And he lied to Sylvia about it. My mother believed that ‘his innate prudishness prevailed over his instinct to help, that he did not want his arm memories of Tim White tainted by some of the phrases in his letters “you don’t know what muddle I am in with work and dogs and drink…’ “My GOd, what couldn’t I do to a bottle of Irish!” “a glorious but dumb cock teaser :I think i did write to Mary about my new (supposed) son… I have never seen him.” “I feel I owe you a letter unless i wrote you one last week when too drunk to nitoce it’ “Norman [my uncle] exhausts me as I do you and ‘To a recluse like me it is too hard work answering questions for give days on e ery available subject indluding the copulation of bulls…’

In other words, my grandfather stuck his head in the sand. He couldn’t cope with the true White who was so deeply troubled by his own sexuality (he once attempted a ‘normal’ marriage) and his spiralling alcoholism.

From the Channel Island of Alderney, he told Raymond that it was “about 900% nicer then Éire” [interesting that he calls the land by its real name] and in 1948, the absolute clanger: “Are you, Raymond, willing to illustrate my whole King Arthur antholgoy (Approx. 250,000 words) with at least twnety medieval pictures?” The Once and Future King, being one of my favourite books in the world! My grandfather had the honour of being asked to illustrate it, but he seems to have passed up the offer! I wonder why on earth he didn’t. Was it that he felt he could not work with White, at least the troubled side of White.

Raymond heard no more, (not surprisingly) but the brooding photograph of White which Raymond took at Trim in 1945 pleased White so much that he used it for publication and it was used for some of the many obitiuaries that appeared in 1964. He was 57 when he was found dead in his cabin during a Meditteranean cruise.

His 1938 poem says it all, and seems to me almost like a suicide note:

Of hapless father hapless son

My birth was brutally begun

And all my childhood o’ver the pram

The father and the maniac dam

Struggled and learned to pierce the knife

Into each other’s bitter life.

Thus bred without security

What dared I love, whom did not flee?

His creative decline in the final years of his life had come along with his growing financial success with the production of the musical Camelot (1960) that was based on his Arthurian cycle. It seems that Ireland was not the scene of his declining health, like it was for poor Hopkins and Wittgenstein, but Merry Old England. At least little old Ireland wasn’t to blame for depression, drink and suicide, this time.

Here in this blog, there are things revealed that nobody has seen or read before. Even I didn’t know about White and my grandfather, til I rummaged around in the attic…. ALL MY WORK IS FREE. ISN’T THAT SOMETHING! I DON’T WANT TO CHARGE PEOPLE, PUSH THEM INTO A CORNER TO SUBSCRIBE IN A PAID FASHION SO IT IS ALL FOR FREE! BUT IF YOU FEEL LIKE BUYING ME A COFFEE, SOMEBODY FINALLY TAUGHT ME HOW TO INSTALL THE BUTTON…

Truly facinating blog, such great insights!

Fascinating! My family also exiled themselves from Ireland, then Scotland... I have lived in years of exile from London and I am thinking of exiling myself back to Ireland. I had no idea Joyce was teaching English whilst he wrote in Trieste. I feel a bit miserable as I just left Spain because I hated teaching English! Keep up the good work. I was thinking about signing up for your mythology and writing course. Can you send me more details about that?