I took my father’s watch to Rome with me, when I ran away at 19 years old. I was terrible for just borrowing things and worse for losing them. The watch he was given by his father, was, I thought he told me, given to him on ‘The Night of the Big Wind.’ But that was the name for the ferocious storm of 1839.

I like how they write about it on Secret Ireland:

“Ireland remembers her storms the way she remembers her saints: with reverence, fear, and a hint of poetic flourish. But none of her tempests, not before and not since, has cast a shadow as long and as ferocious as the Night of the Big Wind, or Oíche na Gaoithe Móire, on January 6, 1839. It was a night when the island quaked under nature’s merciless howl, a night when the fury of the heavens raged unchecked, reshaping the land, its people, and their memories forever.

Did I remember it all wrongly? He couldn’t have been talking about that night of that storm– he was far from being even born– about 90 years off. He was referring to a windfall of some sort, not a storm. But then, I realised, there was of course a great storm in 1947! There really bloody was. Six hundred people died buried under snow in February 1947. I don’t know why my father didn’t even mention it to me. ‘The Blizzard’ of February 25th 1947 was the greatest single snowfall on record, lasted for fifty consecutive hours, smothered the entire island in a blanket of snow that drifted until every hollow, depression, arch and alleyway was filled and the Irish countryside became a vast ashen wasteland. A sea of white. Freezing temperatures solidified the surface and it was three weeks before the snows began to melt.

And we thought Storm Darragh, Ashley, Eowyn (why is it spelled like that? Who baptises these storms, anyway?) were bad. Not a patch on 1947 or 1839. Not a word about Climate Change. And in those days you heard about the storm afterwards, not days before.

For whatever reason, my father must have been more focussed on the windfall that befell my grandad that year, and not the snowstorm that killed 600 people. Besides, he was very distracted by the family ‘guest’, an Abwehr spy called Herman Goetz, who had hid out in his family orchard. Why, you might ask? It’s a long story. Now the spy was released from the Curragh Internment camp (where Grandad had also been held for two years) and threatened with deportation by the Irish authorities, took his cyanide capsule (which my grandfather Jim had kept for him) and dropped dead in the Garda station. Goetz’s funeral was in May 1947. So that year was a big one, with a mammoth snowstorm, the death of a Nazi spy and of course Indian Independence from the clutches of the Crown! But it was also the year of a housing market upturn, when my Grandad Jim sold the house in Shankill for £5,500 and spent the rest of the time throwing money around like

‘snuff at a wake. He gave watches to my brother and myself and I got a pinstripe suit from FX KElly on Grafton Street . We moved into No. 43 Fitzwilliam Squiare and my brother (Gerry) went off to Glenstal Abbey.’ Donal O’Donovan, Little Old Man Cut Short

Anyway, the watch. I took it to Rome. I’m not sure why. To bring a piece of my father with me? Probably wise, considering the trouble I got into. All had been well for me, for the first half of that year in the early ninties, working for Globus magazine on Via Kircher in Parioli, and living with Lady Cecelia Foley, near the Catacombs of Priscilla. That part of the story is in Roma, Part I. Well enough, anyway. But it was when I crossed the beautiful bridge over the River Tiber to Trastevere and wandered through its narrow, cobbled streets, that everything changed for me in Rome.

I’m not sure how the transition happened. It was high summer, time perhaps for my nineteen year old self to kick off her lodger-and-working-shoes, to embrace her inner vagabond. Because I know I didn’t go back to Parioli on the bus to write more travel features for Globus magazine THAT summer. I don’t remember handing in my notice to my boss, Laura Reffo and yet I had a reference, so it must have ended amicably. I still have it. I don’t remember even how I left poor Lady Cecelia on the Via di Trasone near the Catacombs of Priscilla. What did I say to her ? I’ve found a better option - I’m thinking of taking to the streets. I hardly think I said that. But how I ended up there and why, is still a mystery to me. You’d better read Roma I if you have no idea what I’m talking about.

It might have been Luigi, my one and only student of English, (who I probably met through Globus), that first brought me to Trastevere but if it was, it would have been in a Fiat. I love the memory of walking over the Tiber on that beautiful bridge the Ponte Sisto, which connects Via dei Pettinari in the Rione of Regola to Piazza Trilussa in Trastevere. I hope that was how I entered that strange and ancient quarter of Rome. You see, Luigi didn’t walk. He drove. He had very large, bushy eyebrows and he lived somewhere on the outskirts of Rome (I can’t remember where now, I just remember his mother who fed us from a large, stainless stell pot. Pasta, yes.) He brought me to a family confirmation feast one Sunday- there were about six courses to it, with roasted creatures on silver platters.

We did go to to a Trastevere restaurant, might have been Tonnarello’s, I have no idea. Interesting if it was, since that restaurant is right around the corner from the Bar where the Vagabondi hung out. Wherever we were, Luigi said it was the best Roman restaurant. All I can remember was the darkness of the place, and the long tablecloths that swept the ground, the waiters milling about with trays of drinks, an air of superiority about them, working in Rome’s ‘best restaurant’. Was it Tonnarello’s ? I have to admit I don’t really care and I have no idea what I ate there anyway. Luigi brought me to many Sicilian, Sardegnan and Roman restaurants. In one of them, I think it was Sicilian, the waiters flung plates at each other across the restaurant. We ate large pieces of greasy cheese as one of the many courses and I thought the meal would never end. Anyway, I didn’t go to Trastevere because of its restaurants. I’m not Elizabeth Gilbert. And I wasn’t then, either.

“But we are like Tolstoy’s fabled beggar who spent his life sitting on a pot of gold, begging for pennies from every passerby, unaware that his fortune was right under him the whole time.” Elizabeth Gilbert, Eat Pray Love -2006

I had no idea I had a pot of gold. I threw everything away to find something, and yet I had no idea what that something was. I found fabled beggars, alright- I went to live with them on the streets of Trastevere. My Vagabondi. I may have had something like the shadowed version of Elizabeth Gilbert’s journey in Eat, Pray, Love. Not that she didn’t have her own shadows. I just had different shadows, that’s all.

Perhaps it was only a month that I lived on the streets with i Vagabondi. Tolstoy’s fabled beggars, from all over the world. It could have been two.

Elizabeth Gilbert went to Trastevere to eat, as far as I can understand. To find pleasure. She did it successfully, living as in Dolce fa Niente for a while, shedding a bit of her New York work ethic, but it didn’t work. She ended up descending into a depression. She got a message through her magic notebook that told her she was loved. That she would always be taken care of. I had no such notebook. I have no idea where any of my belongings were at that time, and how I actually did drift through the streets of Trastevere with the Vagabondi. I was not there to find beauty, nor pleasure. But to find something on those streets and in those people that gave me permission to wander, to not belong, perhaps. To be nobody.

Eat Pray Love focusses a little myopically on the experiences of one American divorcee in Rome. The success of such books can actually damage places like Trastevere and Bali. Some people for some reason want to relive Gilbert’s experience, and not to live their own. Or, they just want to Eat. Which is fair enough. Most sentient beings want to eat. However, the legacy of the book becomes part of the machinery of tourism. To eat where she ate, to see what she saw. I was a lot younger than Gilbert ( I was in Rome over a decade before she was) and I hadn’t savings to lavish in restaurants. I was starving for experience, and got myself into trouble for it. Ostensibly, I was a good girl, I had finished one year in University College Galway, and was transferring to University College Dublin so that I could study the History of Art, along with English. I found the opportunity, in the gap, to run away. I had a boyfriend (we relentlessly fought, broke up and this was a long break, thought to be the end). It was not like Gilbert’s divorce, but it did catapult me off the island, to a country that had me besotted. Running away was a thrill, fleeing family shadows and cobwebs. I wanted to get lost like this, never being accountable to anyone. If my parents had known, they might have done something. But they knew nothing, and they will never know now.

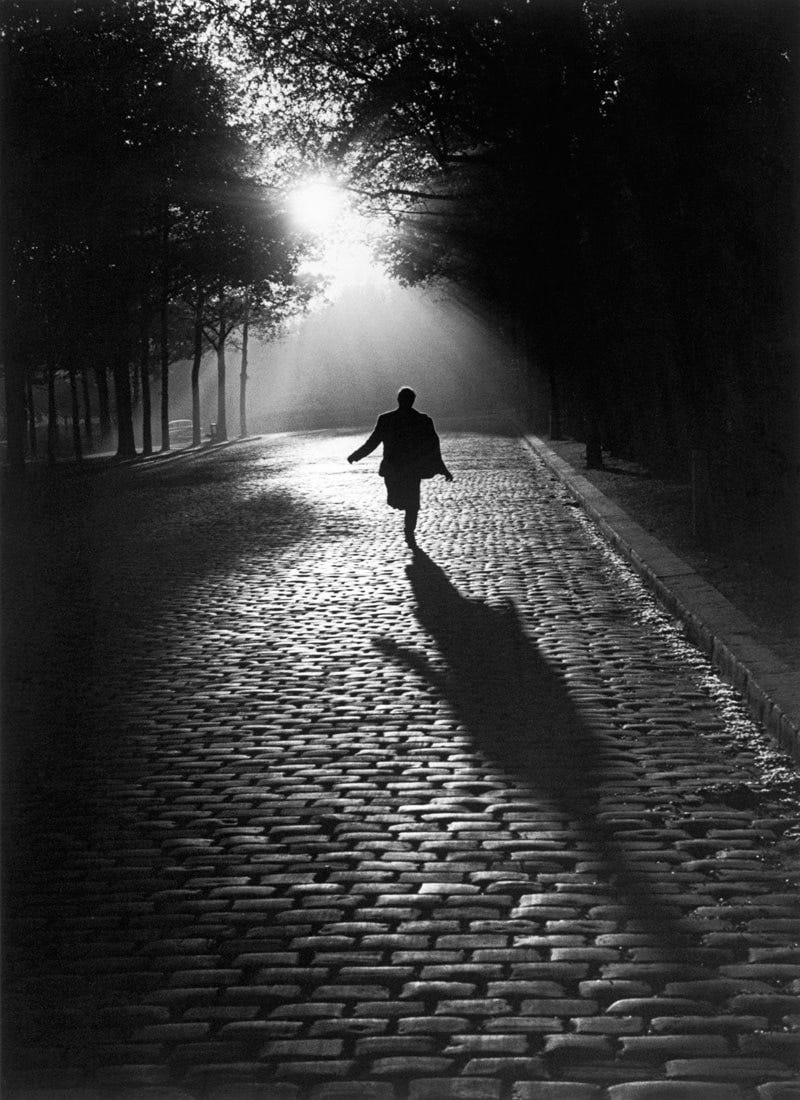

My vagabondi friends who slept on the ledge of the Tiber had all been led to this Roman quarter, driven by the same displacement. Home was a strange thing to be feared, a heap of stinking memory in the far distance. Here, you could belong by not belonging, be eternally displaced on the beautiful streets of Rome, with its mammoth ruins like the teeth of an ancient monster, its sublimely beautiful churches, fountains and buildings. I think we wanted to be devoured by Rome.

In Olga Tokarczuk’s I Vagabondi, the narrator confides that since she was a child, when she watched the flow of the Oder, she wanted only one thing: to be a boat on that river, to be eternal movement. The book follows nomadic lives. Like Chopin's sister, who takes the musician's heart from Paris to Warsaw, to bury it at home; the Dutch anatomist who discovered the Achilles tendon and uses his own body as a research ground; Soliman, kidnapped as a child from Nigeria and brought to the court of Austria as a mascot, finally, after his death, stuffed and put on display; and a people of Slavic nomads, the Bieguni, the vagabonds of the title, who lead an itinerant life, counting on the kindness of others. An interesting book that I confess I have not read yet, but find the idea far more intriguing than Eat Pray Love. I’m not all down on Gilbert, I actually really like her, especially her wisdom in Big Magic. Eat, Pray Love is just too much of a cult book, and it has sent too many Americans to Trastevere and Bali. India can manage and subsume the Eat Pray Love-ers, but these smaller places can’t. We have to have our own journeys. Oh and the movie was awful.

I’ve always been a friend of food. I probably put on about seven pounds in Rome when we were shooting. I ate a lot of pizzas in Naples. It was just great. But it was hard on take 10 on a giant plate of pasta…It is a challenge and I love a good meal. Someone suggested I had a spit bucket but I can’t do that because it makes me gag. It just grosses me out. - pearls of wisdom from Julia Roberts, while shooting Eat Pray Love in Italy

Olga’s book intrigues me, because of the kind of Vagabondi it follows. The book has an authentic ring to it. Not that Gilbert wasn’t authentic. It was because she was, in fact, that her book sold millions. She told the truth of how she was and how it affected her and where it sent her, both within and without. It was just a little cheesy, that’s all.

I remember going to Trastevere alone on the tram to the cinema when I still lived with Cecelia Foley by the Catacombs. I saw Stephen King’s Misery there. ‘Misery. Non Deve Morire’ I remember the Intermesso, when the red curtains closed and out came a little man with a red pillbox hat and a tray of gelato tied around his neck with a strap. I’m sure I saw something else there. Maybe it was after that, that I met my Vagabondi friends. Maybe I turned the corner to the bar, and got talking to my Vagabondi. I don’t remember.

These vagabondi had taken to the streets of Rome from Berlin, London, Glasgow, Belfast, Madrid, Paris and Malaysia and Ireland, and Germany and France. There were glamorous Italian junkies that looked like models, English men with dogs who had lived ten years in Rome but could barely ask for a Capuccino, there was a German man who had but one suit that he wore eternally, so that he could stand outside hotels and use his English accent to proclaim to wealthy tourists_

“Excuse me, I appear to have lost my wallet,” he would say in an English accent, tapping his breast pocket. “Could you possibly help me with the cost of a hotel room?” It worked, in those days. People had cash. They gave it to him, out of pity. He took their addresses, and threw them into the bin. He made hundreds if not thousands in a week. But he was living like this because he had lost his wife and children in a tragic bus accident in Spain. He survived, and left everything else behind. I wish I could remember his name, but I can’t. I can’t actually remember any of their names. Even the renegade British soldier, who had deserted the Army. He was Scottish, had fled Belfast, revolted by what the British Army were doing there. I saw him as a conscientious objector.

We all slept on the banks of the Tiber, and sometimes in a derelict garage. The Carabinieri would come and swoop to check our documenti, but most of the time we fled like a murder of crows before they could catch us. I have no idea if I still had a permissio di soggiorno by that time. I was lost. Running around the streets, or sitting on them or sleeping on the River Bank. I remember one night an old woman in a white dress on the Tiber River bank, speaking to people who weren’t there. I felt sorry for her, and a little haunted. The vagabondi said she’d been let out of the mental home, and she was always talking like that. Maybe she was in a dressing gown, and not in the white dress in my memory- but she certainly wasn’t dressed to face the world. I remember thinking how awful it must have been for her, wandering along the Tiber, talking to ghosts.

And then I had an awful thought, that I could be her. I had that thought, walking through the Piazza di Santa Maria in Trastevere, towards the Basilica. What was I doing here? What was my purpose? I had no desk to write on. I had left Lady Foley. I had left my job. I was lost. Maybe I wasn’t so unlike Elizabeth Gilbert and maybe she had better ways of dealing with herself than I did. I didn’t think that then, of course as she hadn’t written Eat Pray Love by then…but I had lost my own magic notebook.

Rome-the city of visible history, where the past of a whole hemisphere seems moving in funeral procession with strange ancestral images and trophies gathered from afar. -George Eliot

Things like this aren’t too problematic, when you are nineteen or twenty, and you come from a background of a certain type. It’s not like I lived in real desperation, on the banks of the Tiber. Not like that poor woman who spoke to ghosts. Nor, as I was reminded by my friend Tony Foutz, who lived in Rome for decades from the sixties, that the Ponte Sisto was known as Ponte Polacco (the Poles’ Bridge) as it was bracketed by scaffolding and the Polish émigrés looking for work were living under the bridge. Back then, Tony and his wife Victoria lived next to the Basilica Santa Maria in Trastevere on the Vicolo del Piede.

But, I was in some measure of trouble back then. Some kind of a pickle with a Roman girl who loved the Scottish ex-soldier. She wanted revenge. On me. I wasn’t sure how to handle it. She went for me. One night I was pulled into a car outside that Bar where we all hung out. I was brought, with the Scottish lad, to a Sicilian’s apartment. That was when she pulled my arm out the car window, and my father’s watch flew off my wrist. We drove off down the narrow streets to the Sicilian’s house, who rushed us in the door of his building. The Sicilian didn’t like the Roman girl, she’d ratted on him about something to the Caribinieri. You can imagine. After a while, his intercom rang. He pulled out a sword, gleaming in the night. His Spanish girfriend, who must have been used to him, said ‘non vale la pena.’ It’s not worth the trouble. He said that if it was that Roman girl at the door, he’d use the sword. Don’t bother said his girlfriend, with a shrug of her shoulders. I thought she was very cool, sitting on the sofa like a diva, hardly bothered by all this drama. He was probably always pulling that sword out of its scabbard, just for the fun of it, for the taunt.

The next day, I knew the watch was gone. I wondered if the Roman girl had found it on the cobblestones and sold it for revenge, my father’s windfall-watch gone forever. I suppose I will never know. There was a Malaysian man called Patrick who used to hang out at the Bar, and I told him I had to leave Rome soon. Could he possibly send me a postcard (to Ireland) and tell me if the watch was ever found? I gave him my parents’ address. I showed him where the car had pulled up, right at the corner where the Bar was. It was here, I told him, that she yanked my arm out of the car and the watch flew off my wrist. There was another Patrick, a West Brit addicted to heroine, who said sleepily that he’d help too, but he was a lost cause. I wondered who his parents were, which crumbling mansion did he run away from in Ireland.

I went to phone my Aunt in Amsterdam, who lived in a suburb called Huizen, where I had been many times as a child. I needed to go there, to get out of Rome. She said take the train, we’re waiting for you.

A week or so later I called home to see if my parents even remembered who I was. My father said sternly that a postcard had arrived from Italy. It said–

Hi Siofra, I didn’t find your watch. Sorry. Patrick.

That was the end of that. They had no idea that I had left my job in Globus, and my lodgings with Lady Foley. That I had slept on the banks of the Tiber, and in garages for weeks. That I was trying to escape the clutches of an enraged Roman girl, I did not tell them. That I was in the car of a Sicilian drug dealer with a Scottish deserter of the British army, I did not tell them. That the Sicilian had a gleaming sword he threatened to lop the head off a Roman girl, I did not tell them. They only knew that a postcard from the edges of my madness had plopped into their letter box, telling them that the 1947 Night-of-the-Big-Wind watch was gone. Forever. Lost in Rome.

Before I left Rome, I was turning on a street corner with the Scottish ex soldier, and she was there, waiting. She hurled a curse at me, and poked her two fingers right into my eyes. I have never forgotten it. I know what it meant. It was not long after that, that I left for Amsterdam.

Rome is the city of echoes, the city of illusions, and the city of yearning. -Giotto di Bondone

And so, being back in Rome after decades, I searched for the piece of me I lost there. I found the Bar, I found the Piazza where the gypsy Roman girl chased me. I went into the Basilica of Maria In Trastevere and lit candles. For me, for all of them. I vagabondi.

THank you for reading my blog! All my work is free still, so if you do feel to support my writing, please do!

“Rome will exist as long as the Coliseum does; when the Coliseum falls, so will Rome; when Rome falls, so will the world.”

-Venerable Bede, Saint

Verify email what's this. Anyway enjoyed Rome 2

Such a good account, the vagabond referred to, well it seems they were mostly destitute and homeless except possibly for the one with the Spanish girl friend. However anything about Italy is interesting, such an interesting country. As you say the churches are beautiful especially the inside of the one shown, never seen a pleasent etc church interior. Sad you lost your father's watch, originally from your grandfather, of such sentimental value. I've lost two watches unexpectedly coming off my wrist I have not heard of Elizabeth Gilbert but your accounts are obviously just as good. I'm intrigued by the account of the Great Wind of 1839 and that house seems dangerously near the sea! Yes, I too often wonder how the storms are named. Now I didn't know the snow of Febuary 1947 cost so many lives here in Ireland. The recent storm Eowan or whatever she was called was said to bbthe second strongest since 1839 especially in the West. To return to Italy Tresrare looks, Italian food is usually good you did not seem to come off so well with it