The Frog Prince

The Call to Adventure, the Underworld and the Serpentine Beings

Should you listen to an amphibian who speaks in riddles? One who incites you to adventure? One who trips you up into an unknown, unsuspecting world, and in which you, the heroine of the faery tale, are thrust into relationship with unknown forces of nature.

‘The Frog Prince’ is perhaps, of all the classic fairy tales, the one that is in its essence a ‘fairy tale’, with the ‘living happily ever after’ sweetly tying the knot at its conclusion.

THE FROG PRINCE

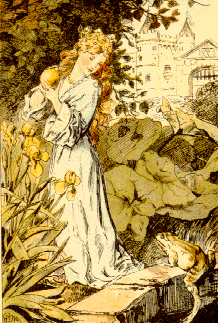

A young princess is playing with a golden ball by a woodland spring one day, throwing the ball in the air and catching it.

She fails to catch it and it falls into the spring. She looks into the water but it’s so deep that she cannot see the bottom of the spring, and so cannot retrieve her ball. She’s so fond of her little ball that she sighs and says she would give all her fine clothes and possessions if she could get it back.

A frog’s head emerges from the spring waters. He asks her what she is looking for. She’s lost her golden ball in the well, she tells him. The frog says he will get it back for her, if she promises to let him come and live with her, and eat from her plate, and sleep on her pillow at night. So desperate is the princess to recover her ball that she hastily agrees, and in doing so is contracted to the promise to her amphibian friend. Only because she thinks he will and never can leave the well.

The frog disappears under the water and emerges a few moments later with the princess’ golden ball in his mouth. As soon as she’s taken her ball back from the frog, the princess runs off home, forgetting to honour her end of the bargain.

When the princess gets home, she thinks she’s safe from the frog, but that night, he turns up at the door, and speaks to her:

‘Open the door, my princess dear,

Open the door to thy true love here!

And mind the words that thou and I said

By the fountain cool in the greenwood shade.’

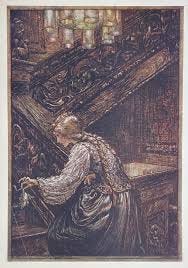

When the princess opens the door, the frog is sitting there on the doormat. Slamming the door in horror, the princess runs to her father, the king, and tells him about the promise she made, and that the frog has shown up on their front doorstep.

The frog knocks again at the door, saying:

‘Open the door, my princess dear,

Open the door to thy true love here!

And mind the words that thou and I said

By the fountain cool in the greenwood shade.’

The king tells his daughter that as she made a promise to the frog, she has to honour it, so the princess reluctantly goes to the door and lets the frog in. She lets the frog eat from her plate, and then, that night, she lets the frog sleep on her pillow.

The next morning, the frog lets itself out the door, and the princess heaves a sigh of relief, thinking that she’s seen the last of him.

But that night, the frog returns, and once again eats from her plate and sleeps on her pillow. The next morning, he leaves again, but that night he returns, and spends a third night with the princess. Things happen in threes.

But the following morning, the princess woke to find herself gazing, not at the frog on her pillow next to her, but at a handsome young prince, who tells her that an evil fairy had cast a spell over him, which transformed him into a frog.

Of course, the only thing that could break the spell was if he could entice a beautiful princess to take him out of the spring and let him spend three nights in her home. Then he would magically change back into a prince. And yes, he would offer the princess his hand in marriage. She would accept and they would ride off into the sunset to live happily ever after in the prince’s father’s land.

Here is a recording of me reading The Frog Prince, as written by Joseph Campbell in The Hero With a Thousand Faces- or at least the beginning of it.

A blunder reveals an unsuspected world.

As Freud has shown, blunders are not the merest chance. They are the result of suppressed desires and conflicts. They are ripples on the surface of life, prodcued by unsuspected springs. And theres may be very deep- as deep as the soul itself. The blunder may amount to the opening of a destiny. Thus it happens, in this fairy tale, that the disappearance of the ball is the first sign of something coming for the princess, the frog is the second, and the unconsidering promise the third- Joseph Campbell, the Hero with a Thousand Faces, Chapter One, The Call to Adventure

The frog is the herald, the crisis of his appearance is the Call to Adventure.

The herald’s summons may be to live, as in the present instance, or, at a later moment, to die. It may sound the call to some high historical undertaking. Or it may mark the dawn of religious illumination. As apprehended by the mystic, it markes what has been termed “the awakening of the self”. In the case of the princess of the fairy tale, it signified no more than the coming of adolescence. But whether small or great, and no matter the stage of life, the call rings up the curtain, always on a mystery of transfiguration- a rite, or moment, of spiritual passage, which, when complete, amoutns to a dying and a birth- Joseph Campbell, The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Chapter One, the Call to Adventure

All the trappings of the faery tale are there- the beautiful princess, the handsome prince, the marriage at the end, the magical transformation, the evil fairy/witch, the importance of the number three, and the idea of undergoing a trial before the happy resolution materialises.

The Call to Adventure involves the Dark Forest, the great tree, the babbling spring, the appearance of the carrier of the power of destiny.

We recognise in the scene the symbols of the World Navel. The frog, the little dragon, is the nursery couterpart of the underworld serpent whose head supports the earth and who represents the life progenetive, demiurgic powers of the abyss. He comes up with the golden sun ball, his dark deep waters having just taken it down, like the great Chinese Dragon of the East, delivering the rising sun in his jaws, or the frog on whose head rides the handsome young immortal… - THWTF Joseph Campbell

And then, there is the Kiss. A kiss can transform a person from hideous monstrousness into a state of beauty and normality, a notion very popular in the Middle Ages. In his Travels, John Mandeville recounted the tale of the daughter of Hippocrates, who was turned into the ‘forme and lykeness of a gret Dragoun, that is an hundred Fadme of lengthe’, and was destined to remain in such an uncomely state until a brave knight ventured to kiss her and release her from her dragonhood. So there we have the story, in reverse.

John Mandeville’s book claims that he crossed the sea in 1322 to Turkey, Tartary, Persia, Syria, Arabia, Egypt, Libya, Ethiopia, Amazons, India, China… he may have been an invented author, since his travel memoirs derive from other travel books such as La Flor des Estoires d'Orient of the Armenian Hetoum who, in 1307 dictated this work on the East, in French at the court of Poitiers. The story of the fortress at Corycus, or the Castle Sparrowhawk, appears in Mandeville's Book, a story that comes into the story of Melusine.

Interspersed, especially in the chapters about the Levant are the stories and legends that were told to every pilgrim, such as the legend of Seth and the grains of paradise from which grew the wood of the Holy Cross, The Dragon of Cos, the shooting of Cain by Lamech and the Castle of the Sparrow-hawk, which appears as I’ve said the the tale of Melusine.

Melusine, the mermaid-faery-naga whose beauty tempted mortal (noble) men. As in Asian royal lineages who claim naga (serpent) descent, so did the royal houses in Europe. Take the Merovingian clan, who claim descent from a sea-beast called a quiontaur: ‘In the event she was made pregnant, either by the beast or by her husband, and she gave birth to a son called Merovech, from whom the kings of the Franks have subsequently been called Merovingians.’ (7th-century Chronicle of Fredegar)

The Plantagenets, the Anglo-Norman dynasty that began the conquest of Ireland, claimed descent from Melusine. She was a shape-shifting beauty sometimes represented as a mermaid, other times a naga-like being and less frequently, as a full blown dragon(-ess). Melusine is sometimes known, especially in the House of Anjou (Plantagenet), as ‘the Demon Countess’ according to the moralistic chroniclers of the middle ages. She met the Anjou Count whom she married (a Grandfather of Henry II Plantagenet), like the Princess, by the well. Except that it was she that was the murky serpentine being, not he.

Melusine ‘legends’ are connected with Northern France, Poitou, the Low Countries and as far east as Cyprus: the French Lusignan royal house that ruled the island from 1192 to 1489 claimed to be descended from Melusine. Other noble lines descend from her- the House of Luxembourg from the Holy Roman Empire and the Counts of Anjou, as we have seen.

Melusine, the ‘Demon Countess’ of Anjou, had a grandson called Geoffrey Plantagenet, who shaped the future of England and France by supernatural (demonic?) skills in military strategy. Despite its abundant beauty and (fig trees, vineyards) the Angevin territory was regarded as savage by the Normans they saw them as people who desecrated churches, murdered priests and had disgusting table manners (with falcons at the table hunting live birds in pies). The Counts of Anjou were ferocious and warlike, had a huge greed for land and power. They were the first conquerors of Ireland, of course, led by King John (Lackland) Plantagenet. We have nothing to thank them for.

The tale of the Frog Prince had been known in Scotland since the late Middle Ages, although it would only be referred to in print by English writers from the eighteenth century onwards, and it was really in the nineteenth century, when the Brothers Grimm set down their telling of the tale, that the story became a firmly established fairy tale.

The dalliance between the underwater/ underworld, the serpentine world and this world, the whole metamorphosis from the ugly (back) into the beautiful seemed to have been a bewitching one, to our ancestors. Honouring promises and contracts between those worlds held punishment and misery if reneged.

An tIcke of far Wight is spot on on woyal dragoons then. He bangs on so of Lady Die catchin Firm members doing the shapeshift.... Fine Prince Thing....then pffff magic dragon.... or other genus o'weaptillion.....

Fascinating as usual Siofra

Thanks for sharing. Joy B