The Old Man and his Chicken

A Tale of the Floods

Well, first of all, Lá Féile Bríde Shona Dhuit. I’m not going to have to tell you that this blog has nothing to do with Brigid, but you never know. No, nothing. It’s a story and a tale I wrote years ago, in 2001. At least I think that is when I wrote it. I never dated it, so can’t be sure but given that it was around that time I was in New York and that strange event with the Towers had occured. The other strange and momentous event was the reinterment of the bodies of the ‘Forgotten Ten’, the executed men hanged by John Ellis (he must be named) in Mountjoy over the period of 1st November 1920 when Kevin Barry was hanged and on into 1921, where Ellis hung men in pairs, like Frank Flood and Thomas Bryan (Boy George O’Dowd’s Great Uncle was the latter). So they removed the remains that had been in Mountjoy Jail for 80 years or so, and brought them to (mostly) Glasnevin in a great stately funeral the likes of which you would never see in today’s Ireland. If you see TG4’s wonderful ten part documentary about the Ten Forgotten Men. If you see clip at 10 mins in, the wonderful but late Kevin Barry Junior and my father speak about Kevin Barry.

I was supposed to be at that funeral. But I have no recollection of ever being aware of it at the time, considering that all of my family were there. But in those days I was on the run from Irish history, which my father had always rammed down my throat.

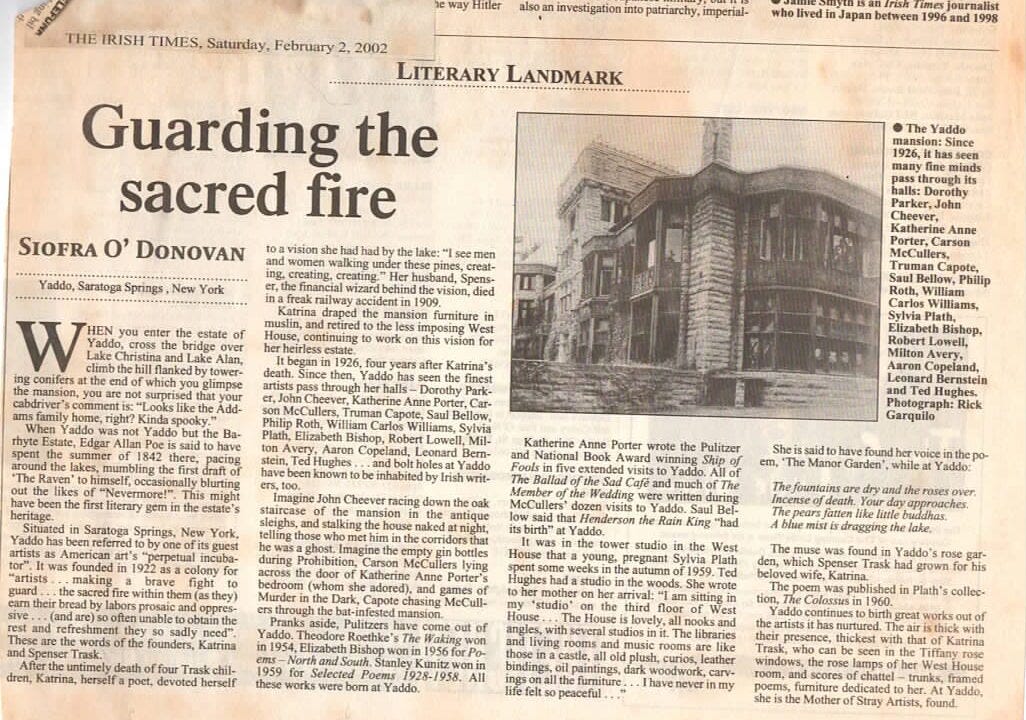

I was living mostly in India, or Poland, depending on where the work took me. But I’d just landed a residency in Saratoga Springs, Upstate New York, called Yaddo, where Sylvia Plath, Carson McCullers and others had done many a stint along with a rake of other American writers. So Kevin Barry was far from my mind in those days. I think Edgar Allan Poe had been to Yaddo when the Trask family owned the estate. I wrote a feature on Yaddo for the Irish Times, who were nice to me in those days and gave me some work. A distant dream now, and a very different kind of newspaper. No more said about it.

I had the time of my life at Yaddo, and wrote reems in this enormous music room I was given for some reason, with a grand piano and views of the avenues of autumn trees with rich golden brown and red leaves, squirrels rushing up and down them preparing for the winter. I was working on Pema and the Yak at the time. There were all sorts of people there, an Indian novelist who was a Professor of Maths in Texas or somewhere like that, who wrote The Death of Vishnu. Manil Suri was his name. A beautiful novel. Nuala O’Faolain (who gave out to me for some reason I can’t remember) and a host of New York artists and writers who were traumatised by the demise of the Towers and some of whom needed to speak to their therapists on the phone quite frequently (from the call box outside the dining room, so you could hear it all) as they couldn’t write or paint or do anything. I sort of pitied them, and felt slightly guilty that I was raging along in the music room on my first draft, delighted with the dinners and the packed lunches and the company was interesting enough, artists of all sorts. The woman I remember most but whose name is gone with the mists of time was the one with the giant earrings, long hair and long capes and patchwork dresses, a deep voice that told us all of her trauma in the aftermath of the Towers falling.

There was a film maker called Jem, who was a bit grumpy but we went to some field (not just me and him but a few of us in case you are wondering) and watched the shooting stars. I can’t remember the name of this stellar event but it was mesmerising watching hundreds of shooting stars blaze across that night sky in upstate New York.

Oh there was somebody there whose name I do remember, Mr. Carl Bernstein, who was the journalist who cracked the Watergate scandal that brought down President Nixon. I remember we all (as in all the residents, not me and Carl) played spin the bottle one night and the revelations being pretty dull. I was surprised. Nobody was playing it real. Anyway when the inevitable political conversation erupted at the dinner table, I blurted out that it was very wrong of the Americans to invade Afghanistan. There was silence, followed by Bernstein’s remark “Well you would wouldn’t you, ‘cause you’re Irish! ” I’m not sure what he meant. Perhaps he was implying that I was a raving little terrorist because I disagreed with aggressive foreign policies. Anyway, I let it pass. He was working on a biography of Hilary Clinton while at Yaddo, and seemed quite pleased and saw no contradiction at all between his subject, and the matter of world peace. She was, as is obvious now, a war hawk. I was so taken with this crowd of people that I sent them all Christmas cards and have never heard from any of them since. Maybe they all thought I was a raving little terrorist for criticising America’s violent foreign policy that was more than often based on fictional devils with beards that would take over the world if they did not stop them. Anyway, here is a little story that I think you might say, began there at Yaddo in October, 2001.

THE OLD MAN AND HIS CHICKEN

“Where is my chicken? “ said Berlind.

“You ate it.”

“I would never eat my chicken. Who has eaten it?”

“I don’t know. It’s eaten, that’s all. Gone.”

“That was my chicken.” said Berlind. “I want it back.”

“It’s been eaten.”

“I want it back. It was my chicken.”

“I know.”

“Savages.” said Berlind, and he walked out onto the street.

“There was a time,” Berlind said to himself, ‘That people knew the value of chickens. Now nobody cares about chickens. Someone took my chicken, but it’s no mean feat. Times have changed. I have asked, and I have been told that there are floods, great floods to come and wash us away. What will be? The Gospels tell us that there was a great storm at sea, the n those sinking in the boat saw Jesus coming toward them across the water. “Courage’ he said, “it is I. Do not be afraid.’ Exodus, 3,4. But what did Jesus know of the chicken farmer? What did he know of Berlind, the chicken farmer? I am lost. I cannot her the words of God in my ears. The spirit has deserted me and I am left alone in the darkness. What will be? What will become of me, I Berlind, the chicken farmer? Berlind who sells meat or their melas and feathers for their eiderdowns. I feed them foul and keep them warm. Still they do not know the value of the chicken. What is coming? What I see is this: I see myself gripping the splintered edge o a raft, my chickens tied to it with wire in a mesh cage. I can hear the winds and feel the cruel waves hurl me to my death. My bones will snap in the wind like sticks of chalk. I am am weak and old, not ready for the Flood, though I am preparing. I made a raft from the old fence. I have that, at least. I have a raft. Berlind’s raft. I’ll write a sign on it to show them who am: Berlind the chicken farmer. Alone. Just me, and my chickens. Alone, lost at sea with my chickens on a raft. Oh God, there will be nothing but water.

There was a time, I was told, that chickens swam at sea and fish clucked about in the yard. That time is not more. How does a chicken farmer farm his chickens on the waters? He does not. That is the answer. He does not. Berlind will not farm his chickens at sea. I do not understand the sea, I do not understand those waters. I fear it. I fear the sea. I fear it will pour itself over the land and we will drown in it. Whole cities, whole mountains and valleys, villages and towns will drown and under the water they will lie broken at the bottom, choked by seaweed. That is what is the come. I will no longer farm my chickens. My bones will make a crisp snack for a shark, my hate will wither, my gold watch will sink in to the sand and be sucked into the core of the earth where all things disappear.

So I ask: what then, what can I do, when the Great Flood comes and takes us away? What then, how can I farm my chickens? What shall I do then? What is the alternative?

Then the answer came:

“Ducks, Berilnd. Ducks. That is the alternative. That is the best thing.’ And the Great Book was closed.

© Síofra O’Donovan 2001

Thank you for reading my blog. It takes a lot of work, and I never ask anyone to pay for a subscription as you all have enough bills. But if you feel like it, it’s the usual request:

So funny, thank you for always being able to tell a story this way, it’s a real joy to read

Its good to know the value of chickens and the value of a good story , thank you Siofra 🐓