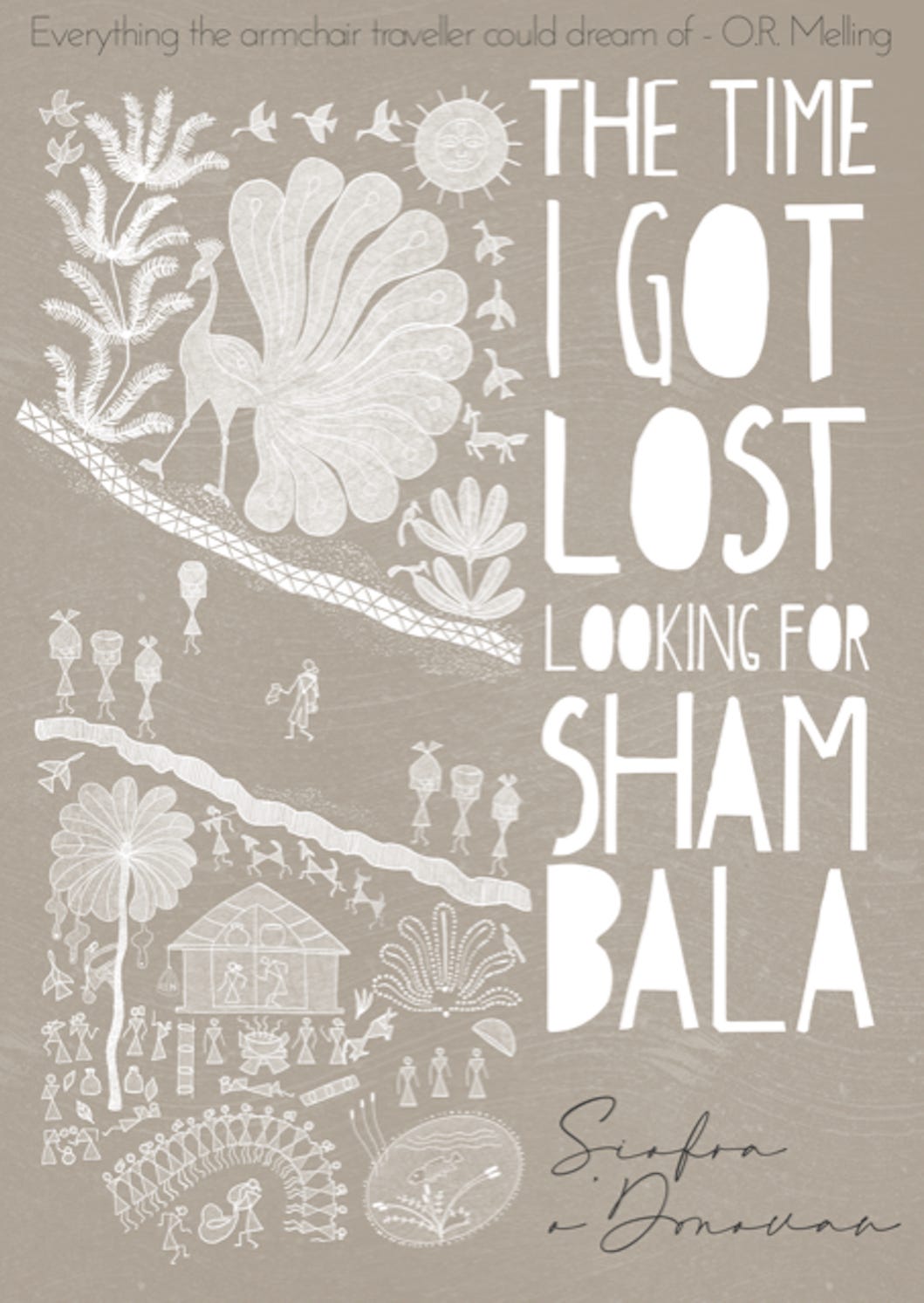

The Time I got Lost Looking for Shambhala

New Book launching soon....

That Time I got Lost Looking for Shambhala is out soon. Watch this space-stack.

Super news. I’ve a new book coming out. Well, it’s a new incarnation of Pema and the Yak, published in 2007 by Pilgrims Books in Varanasi. This is a revised edition with a new title: The Time I got Lost Looking for Shambhala. Because it is about a search, on the part of a people in exile, for their home and it is about my own search for a home. I wanted to find a way of disappearing into another culture, so I stayed there, year after year, for months and months, learning Tibetan so that when I landed up in far flung valleys on the Tibetan border, I could speak well enough to understand the border dialects, and was invited to many a hearth and home, where I collected many a story from many a sort of person… here is the blurb:

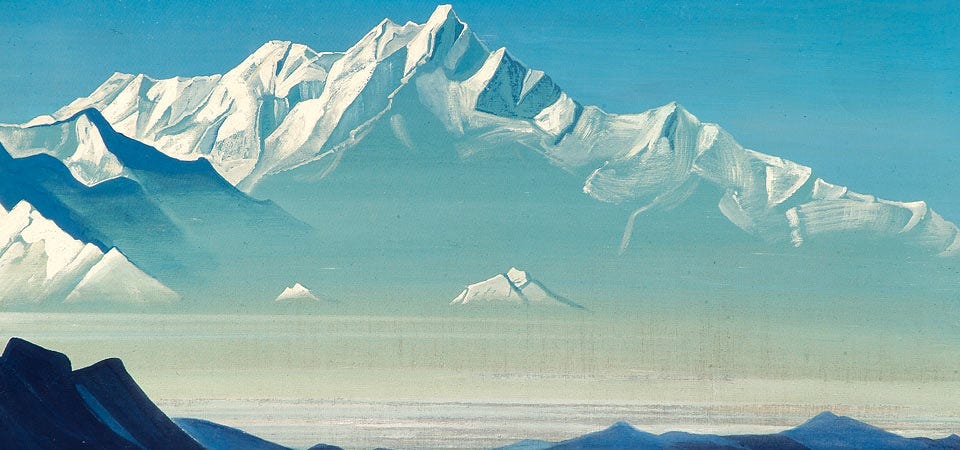

The Time I got Lost looking for Shambhala is the fascinating story of a journey through the Himalaya along the Indo-Tibetan border into the heart of Tibet in Exile. Incredible encounters with oracles, lamas, ex-political prisoners, Tibetan doctors, DJs, nomads, guerilla fighters, painters, poets, spies, missionaries and Himalayan royalty bring the reader into a world of intrigue and, poignantly, to the lost world of Tibet and the hidden world of Shambhala, which lies hidden north of the Himalaya.

Here is an extract:

There were classes in the Tibetan Library in Dharamsala, said Lama Ö. He could arrange rooms. I could become a translator. So that would be my path. No more teaching English in Polish universities. No sitting in an office on some dreary Dublin street, not like that was ever going to happen anyway. I was going to the Himalayas, to study Tibetan, to be at my lama’s side for eternity, translating for him (or so I thought). Thirty years in the west had done nothing to disentangle the syntax of Lama Ö’s English- what he said, he appeared to be saying backwards. Perhaps it is the mark of the best lamas that they do not perfect their English, that they don’t utter perfectly polished and sophisticated sentences. We’ve certainly seen how the smooth operating lamas have ended up.

But that it was me that Lama O had asked, I couldn’t believe. Didn’t he know some competent monks in India who could translate? I said yes to the task, even though I had no idea what I was doing, except that I would be living among his exiled people. There were 150,000 of them living in India, dribbling in over the Himalayas and into India from Nepal and Bhutan since Nehru opened the doors to Tibetan refugees in 1959. Some of them had not survived. The sheer heat of the Indian sun had melted them away, so used to the hard, cold mountain air of Tibet they had been.

I tried to picture Dharamsala, where I was to go and study. I could see steep, winding roads and leaning trees, herds of goats and the shrill white mountains. Dharamsala meant nothing to me, except that it had been the home of the Dalai Lama since 1959. I could see him sitting in a temple at the top of a hill, all alone, his attendants running up and down the hill with silver trays. Yes, my preconceptions were that foolish.

Every time I asked Lama Ö a practical question about the weather in Dharamsala, or the cost of square meal, or the population, he would shuffle away, telling me not to worry, everything would be fine. And I would stare after him, with my heart pounding. But I wanted to know. I wanted to know before I got there. Before. So that my mind could settle. But he persistently ignored me. Not too long before I left I met a woman from London who used to go to India to study Indian singing in Bengal. I had heard her chanting the evening prayers at Jampa Ling, and her voice shone out like a flute among the flat tones in the shrine room. A couple of years ago, she had been to Dharamsala.

“Wonderful” she said rapturously, and put her hand on her heart. Nonsense, I thought, would somebody not tell me a bit of information? I got it out of my London friend that Dharamsala was in the state of Himachel Pradesh, in the foothills of the Himalayas by a mountain range called the Dhaladaur, about four hundred miles from the border with Tibet. It was one of the old Hill Stations, like Shimla and Dheradun that the Raj used to flee to from the burning Plains of India. There were fierce rainfalls in the Monsoon, she said, which left an awful coat of mould on things.

Four hundred miles or so from the border with Tibet. Now, that is what interested me.

I could make my way to the border, once I had enough Tibetan, staying in villages, collecting stories of the old ones who remembered the days when the border was open, when traders and pilgrims passed freely into Tibet. Just a glimpse of the land where Lama Ö had come from. And would I get a sniff of Shambhala? Would some lonely traveller roasting yak meat at a campfire show me the way?

The way to Shambhala. I held onto my secret. Lama Ö gave me a letter of introduction to some lama official in the Library in Dharamsala- an old monk called Ngawang Lungtok, who would organise my rooms. I saw in my mind a trembling old man in burgundy robes emerge out of a cave, handing me the keys to the library. They were from the same village in Tibet, Lama Ö said. Lama Ö laid out a row of letters one the gingham oil cloth table in the kitchen, each with Tibetan scrawled across the envelope. Letters for old friends from his village, some who he hadn’t seen for thirty years.

There was a large plastic bag, bursting with clothes, on the chair. Inside there was a Donegal tweed jacket for a schoolmaster who said he found the winters cold in Dharamsala, and a sack of coloured Aran sweaters for his nephews, whose mother had told them to walk over the Himalayas, out of Tibet, to find a decent school. They used to write to her in Lhasa, Lama Ö said, but they never heard back. As I was leaving, Lama Ö stuffed one hundred rupees into my bag for the taxi from the airport in New Delhi to the Tibetan settlement. Go to Gomang guesthouse, he said. The monks there will show you how to get to Dharamsala.

Pots are impermanent, I said to myself, walking down the drive through the tall trees. I looked back and saw Lama Ö waving to me from the steps of the house, the old beagle at his feet, barking into the garden. He was holding a bell in his hand. The donkeys looked up at me as I passed them by. There were birds squawking in the trees. My music notebook was still in my bag, full of smudged Tibetan letters. I saw myself wade through snow with a cold blue sky above me in the silence. As I turned the bend in the road past the woods, I had the sense that I would not be the same person when I returned to this place again. And I panicked. Did they have face cream in India? Did they have shampoo for dry hair? Did they have nail clippers? What if I lost my nail clippers? Oh, God.

I forgot all about the exiles. And Shambhala. Nothing but hairbrushes, underwear, lotions, dictionaries, mosquito nets, creams, toilet roll, adapters, money belt, knife, a water bottle, cotton wool, a sleeping bag and all the letters and clothes that Lama Ö had given me. Only these occupied my mind. And traveller’s cheques and tickets and visas. Yes, my visa. A six month visa for twenty eight pounds. Couldn’t I stay for a year, I asked the glum lady behind the window, with the sad grey plait that reached her rump and a purple sari that looked like it could do with an iron?

“No.” she said, and stamped my application. Then she threw it in a wire basket.

“I’m going to study.” I said.

She looked at me, horrified.

“Madame this is a holiday visa. You cannot study.”

She shut the window in my face, and left the office.

Stepping off the plane in New Delhi I was nearly knocked down by the deep, hot air. At the passport check point, there was a television sitting on a shelf, with a laminated notice stuck to the wall above it: ENTERTAINMENT. Dancers tore around the screen, falling into each others arms and out again, leaping over fountains, driving motorbikes. Beside me was the Duty Free, where there were some miserable looking bottles of whiskey, and shelves and shelves of Ganesha figurines. Ganesh, the great Hindu God that the subcontinent loves: he who removes obstacles. I asked him for a bit of luck with my taxi booking as I passed the hundreds of figurines. I passed through the passport checkpoint, where it was stamped in italics, by a demure Ms. Amrita Vijay who did not check my face against my passport photo. She did not even look up.

There, there on the creaking, jaded conveyor belt, was my luggage. A red rook sack, now stained with black rubber marks and a coat of dust. My books, my creams, my mosquito net, all these things were with me again. I walked sleepily past a marble Indian god, dancing on a plinth beside another baggage reclaim area.

Past the Arrivals Hall, where there was of course nobody to meet me, and by the looks of it no one to meet anyone else. Outside into the vast heat again, where men hobbled around the taxi ranks with old wooden crutches, and looked straight at me, one with blue film over his eyes, blind, but he still seemed to see me, and held out his hand with three dark, bent fingers as I passed him and stepped into a white ambassador at the end of the rank.

From the white Ambassador that brought me from Indira Ghandi airport, I saw cows sway their hips in the boom of Delhi traffic, as if Delhi was an open field. Thin men in brown shawls sat on traffic islands, shitting. Children sold marigolds on little wooden trays that hung around their necks. All around me, the marvellous stink of drains. An old woman in a green sari walked slowly through a ditch at the side of the road. I felt guilt for the privilege of being driven in a white Ambassador, an old Morris Oxford, sailing through the streets and boulevards of Delhi, my shawl flapping in the wind, the stench of hopeless poverty all around me. In nine hours, I had become a millionaire. My money belt was soaked in sweat.

We passed a white temple with a golden dome. This was the Sikh Temple, the only landmark near the Tibetan Colony. Shortly after we pulled up by a lane way in a shantytown. An old Tibetan man was sitting on a bench, stooped, his fingers curled around his mala beads. Dogs lay around him on the pavement, collapsed in the heat. A pair of monks came down the alley in a rickshaw, driven by a cross-eyed Sikh. So, this was what a Tibetan exile settlement looked like. That jaded man on the bench was a Tibetan exile.

“Where going?” said the cabdriver.

“Gomang Guesthouse.”

He drove down the alley into the maze of markets and tiny streets. There was a plastic sign at the corner of the main market, hung crooked on a pole over a tea stall. Gomang Guesthouse, it read. This road was even narrower. He rolled up outside the guesthouse, in the shadow of the facing building. Some monks were sitting at a table outside playing a board game, spinning red and white plastic discs across a backgammon board. I gave the cabdriver my prepaid receipt and he laughed at me, then glared, demanding bakshish with a wag of his hand. I could see the plastic figure of Ganesh still swinging from his rear mirror. He stood there, blocking my way into the guesthouse, my luggage at his feet.

The manager of Guesthouse came out in a pair of navy shorts and blue plastic flip flops. He did not look like a monk, as Lama Ö told me he was. He smiled, picked up my luggage, and took the receipt from the driver. He had been expecting me.

“Prepaid.” He said to the driver, waving my receipt at him. Indira Ghandi Airport to Majnu-ka-Tila, one hundred rupees paid. The cabman threw himself into his Ambassador, and with his swinging Ganesh, swerved right onto the narrow street, cursing me all the way back to Indira Ghandi airport I am sure.

The manager brought me into the room behind reception, where a pair of sleepy Indian flies glided past me as I came in. The fan spun in slow circles, like a tired old propeller. A pale-skinned monk was sitting cross legged on one of the beds. He had a faint moustache, as if someone had brushed past him with charcoal. He pointed to himself and said Siberia. Tibetans have built monasteries in exile all over India, and there are many monks and nuns from Russia’s Buddhist regions in these. This monk was from the Buriat.

The manager came in with a flask of tea and handed me a cup and saucer and he poured out warm butter tea. Bubbles of fat glistened on the surface. The last thing I wanted to drink in this unbearable heat was Tibetan butter tea. I laid it on the window sill. He walked out again, dragging his blue flip flops across the polished floors. I did not know what to say to the Siberian monk. There was nothing I could say. He spoke no English, and I no Tibetan. Except, of course the old edict Lama Ö had taught me in the kitchen: pum-ba-mi-dak-ba-me. Pots are impermanent. His eyes widened over his cup. It was all I could think of to say, and I had forgotten that I did know how to greet in Tibetan. The Siberian slapped his leg and laughed like a donkey, and repeated the phrase behind his hand, hiding his charcoal moustache. Who was this foreigner lady coming out of a white Ambassador telling him pots are impermanent?

The manager relegated the job of looking after the foreigner to the Siberian monk. He was happy to have something to do, as his train to South India did not leave for two days. He was from Drepung Gomang monastery, one of Tibet’s largest monasteries, destroyed by the Chinese during the Cultural Revolution and rebuilt in the South of India. The Siberian monk took me through the tumbledown streets of the Tibetan Colony, and bought me a plate of meat momos, (Tibetan dumplings), down a back street, which I could not stomach in the din of the heat. He brought me into the kitchens where his Nepali friend was stirring a huge pot of meat. The thick, fatty steam hit my face at the door. The Nepali boy wrapped my momos in newspaper and I put them in my bag, wishing I had never agreed to have them in the first place.

“There,” said the monk from Siberia, “you will have them later.” At least I imagined that’s what he said, and I couldn’t wait to get rid of those greasy bags of fat. Outside I saw a small white dog shake and collapse on the ground in front of us. I thought it had just died of thirst, but it got up again, and continued its hopeless journey through the narrow streets. I left the momos under his nose, and he nuzzled his head into the bag, and began his feast. That evening, at six o’clock, the Siberian monk handed me my ticket for the Potala Bus which travelled daily from Delhi to Dharamsala. He threw my luggage onto the roof and waved at me from the shade of the trees until we had turned the corner of the long road, away from the weary, dingy Tibetan Colony.

The Potala Bus, named after the Dalai Lama’s palace in Lhasa, rattled its way to the foothills of the Himalayas. We stopped, at dawn, by a tea stall. The sky was lavender and the air thick with the too-sweet smell of the Himalayan Queen of the Night, Rati ki Rani, who only opens her petals when the sun has set. I could see the snow peaks on the horizon. I thought that was where I was going, to those peaks, and I imagined the bus driving up the side of a peak, all of us stuck to the back of the bus.

The Potala Bus tore up the last of the Kangra Hills, where I saw whole families washing themselves at a pump by the side of the road, pouring buckets over themselves, soaking their sarongs, washing their teeth and spitting out big white gobs of foam. Finally we got to the jumbling bazaar of Lower Dharamsala, stalls piled high with wire cages full of chickens, steam seeping out of giant pots in the food stalls, pancakes and samosas frying in black pans, drapers, tailors, telephone exchanges, vegetable stalls and hardware shops. Cows ignored the chaos, and dogs lay sprawled out on the streets, or followed some fantastic mission.

At the Bus Station, I stumbled out of the bus, shattered, with a pain in my forehead where my head had been bouncing off the seat rail during scraps of sleep. I had no idea where the Library was. I looked around. A young girl with a tray tied around her neck tore up to me. A sweet, heavy incense cone burned on her begging tray. There was a picture of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and abundance, stuck to the edge with sellotape. I had no change. A curse, in India.

I saw a young man in a black leather jacket and a bandanna sitting on the bench. I went up and asked him where the Library was.

“Up there.” He said, pointing into the trees on the skyline. Dharamsala is full of rolling hills, covered in trees. I could smell alcohol on his breath. I wondered if he knew what he was talking about. I looked into his confused, bloodshot eyes and thanked him as I climbed in to a white taxi van which took me up the winding roads to the Library.

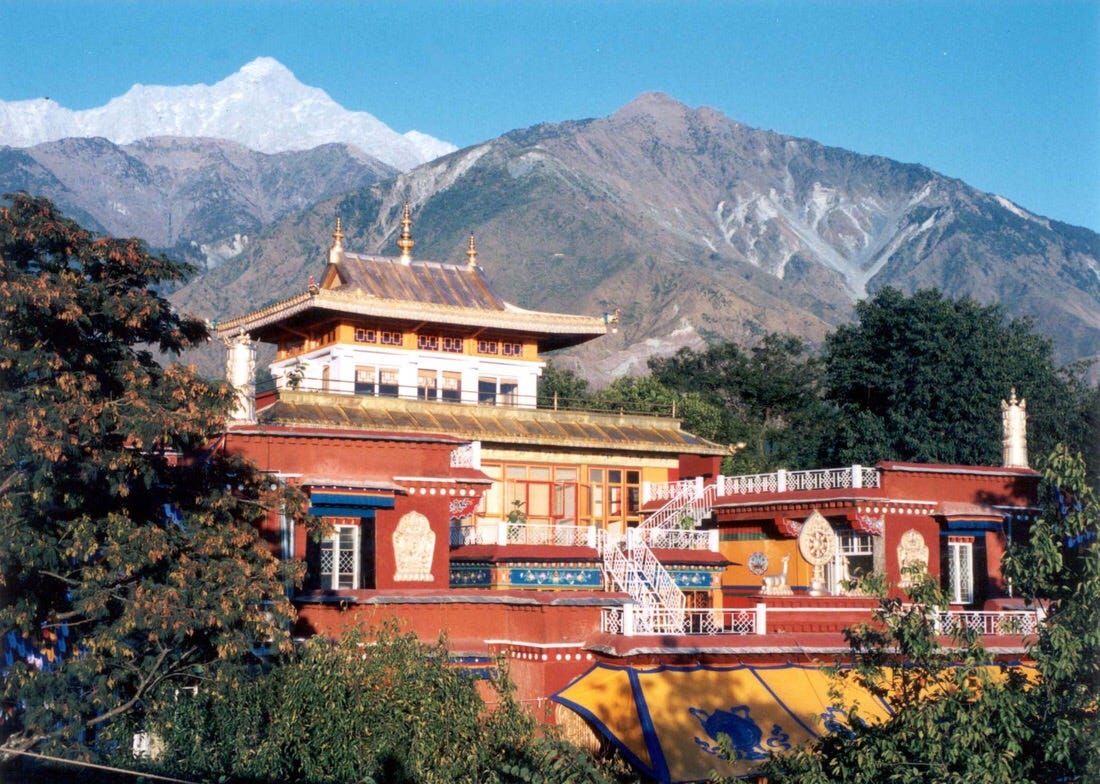

Monkeys scuttled across the thin roads. Children, walking, stared at the van as it passed them. A toothless old Tibetan woman waved at us. We were climbing higher and higher, charging around the elbows in the road. You could see out across the whole of the Kangra Valley, everything submerged in a blue haze, same lazy carrion birds circling around, uninterested. We got to the gates of the Tibetan settlement. It was an elaborate entrance, painted gold with blue, pink, green and red. A maze of latticed designs and birds, horses, fish, umbrellas and bells. Tibetan Letters on the lintel, emblazoned in gold. What it all meant, I had no idea. I could have been entering a casino.

Then I saw the golden pagoda of the Library. Outside, monks walked to their morning classes in blue flip-flops, slapping the ground beneath their burgundy robes. A flurry of white Europeans climbed up the steps from the restaurant. I asked the one in front, with a striped tee shirt and a sun hat and a burnt red nose, where I could find a monk by the name of Ngawang Lungthok. The man with the burnt nose looked at me uncomprehendingly and shrugged. The group shuffled past me and filed into the Library. I dragged my bag up to the balcony and sat down, under the blazing sun.

Where were all of Lama Ö’s friends? I thought they would be here, waiting for me in a line, ready to receive the letters Lama Ö had sent them. A prattle of green parakeets flew over the Library. Beneath the Banyan tree, an immaculate Tibetan woman was preparing momos on a portable table for the lunchtime rush. People walked in and out of the offices of the Kashag, (the Tibetan Parliament in exile), that was in the courtyard below the Library. They carried brown files and stacks of paper. I wondered if those papers held the future of Tibet. Then, two monks, one young and one old, came out of the hive of buildings around the corner, and walked towards the Library steps.

(The Time I got Lost Looking for Shambhala is available here. )

I stepped in front of them and asked them if they had heard of this Ngawang Lungtok? How could I ever find someone with a name like that? Maybe I had got it wrong- I checked the crumpled piece of paper Lama Ö had written his name.

“It is him.” said the young monk, turning to the white-haired monk beside him. He was old. He didn’t meet my gaze, but concentrated his hidden eyes on the ground, where a small cockroach was moving intently toward his sandal.

“I was sent by Lama Ö.” I said, thinking the name would make him wake up, shake my hand, sign the right papers to take rooms. He shuffled forward, avoiding the path of the cockroach and muttered something to the young monk as he passed him by. Then he disappeared, without a word, into the cool hallway of the library. I wondered if I would ever see him again.

The young monk gave me a big smile, and picked up my battered bag. He was stocky and well fed and wore a pair of brass rimmed glasses. He had a friendly round face. He looked studious, but restless. We walked up a twisting pathway under a crowd of tall coniferous trees, through narrow lanes of houses that looked as if they would cave in on each other they were so close. At the end of the lane we climbed up some steps, lined with geraniums and marigolds growing in rusty tin cans. We came to a green door, and the monk pulled back a heavy cloth curtain and plunged a key into the silver padlock which I was sure was made in China. The kitchen was dark. A shank of dry meat hung from the dresser. Through the curtain, there was a room that looked out over the terraced buildings below the library. Over the flat roofs I could see lower hills covered in knobs of green, simmering in the blue heat.

His name was Tenzin, he said, pouring me a long glass of sweet warm tea. He was a monk in Drepung Gomang Monastery, like the Siberian I had met in Delhi. He had come to learn English in Dharamsala. Yes, Dharamsala was the mecca of Tibet in Exile, the home of makeshift English schools for eager monks and potential émigrés. His English School was half way down the lane to lower Dharamsala, on the Khara Dandra Road: The Save Exiled Tibetan Scholars Association. Tenzin patted a pile of text books on the table. I could see he was hoping to get some help.

I was tired, covered in Himalayan dust. He took my glass and told me to go to sleep, handing me a pillow covered in a Chinese pink silk pillowcase with a rose embroidered at the corner. When he left, the green parakeets shot past the window. I heard the long groan of a horn from one of the temples, like a boat coming into harbour. No harbours in these hills, I said to myself.

I fell into a real plunge of a sleep, something I can’t usually do in an unfamiliar place. And I dreamed. It was a dream that was to stay with me for the rest of my journey. I don’t know how I knew that the woman in the dream was called Pema, but she was. She was a Tibetan nomad, and she was walking over a mountain pass thick with snow, with a caravan of yaks. The snow groaned under her boots and sprayed out from under the hooves of the yaks. Down the mountain they went, into exile, in the blue snow under the moon. She asked me, very quietly, to tell the story of her people. Later, she poured me tea from a red flask with a pink rose painted on its barrel.

When I woke up, I was alone. I felt as if I had been visited, and the visitor had just vanished. So, I was to tell the story of Pema’s people. Of how they had walked out over the mountains, through brutal icy passes, and never went back but never stopped thinking that they would, one day, when the Chinese got bored. So many stories had to be told. I wondered, as I stared out the window at the hot, blue hills, if Lama Ö had sent me this dream.

The Time I got Lost Looking for Shambhala is available here.

That Time I got Lost Looking for Shambhala is out soon. Watch this space-stack.

Great reading has inspired me to write about my Bhimtal experiences in the shivaliks 2014