Yours Til Hell Freezes...

Tea leaf Prophecies, Ambushes and Drinking Sprees...

YOURS TIL HELL FREEZES… A STORY ABOUT KEVIN BARRY and Tea leaf Prophecies, Ambushes and Drinking Sprees..

Whatever about those elections across the Atlantic ocean, and our own posse who do not even deserve to be voted for, let’s spin back over a hundred years to another Ireland which was in the throes of a war, the aim of which was to break of the crown clamp. For good.

On the eve of Hallowe’en, 1920, the Barry famly were waiting ominously for the heavy dawn on 1st November, 1920 when Kevin Barry would be hanged in Mountjoy jail, according to the sentence he was given after his Court Marial on 20th October. Many of you probably know the song. Leonard Cohen mistakenly said it was written in 1916. It was written in 1920 during the War of Independence in Ireland.

Kevin Barry was hanged in 1920 in Mountjoy Jail by John Ellis, the executioner appointed by the Crown to hang all men nabbed in the war. Ellis also had a hairdressing business in Cardiff. Kevin was sentenced at a Court Martial in Dublin on 20th October 1920 to be hanged for his part in an ambush on the Monk’s Bakery in Dublin on 20th September 1920.

Here is Kevin Barry Jr. and my father Donal O’Donovan speaking on the documentary The Forgotten Ten, about the reinternment of ten men buried in Mountjoy after execution by John Ellis- the hangman. Shipped over from Wales, especialy for the job. He said after the whole ordeal of hanging all these men, that it was very stressful and he’d like a pay-rise, please. He eventually took his own life.

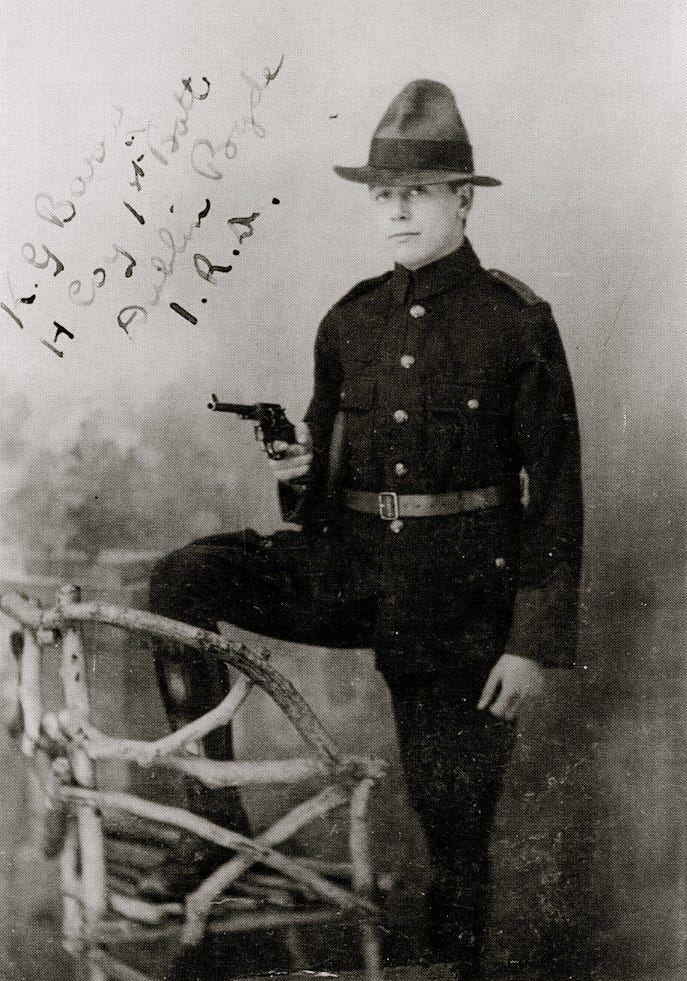

In the summer prior to Kevin’s arrest (20th September 1920), Kevin was also busy in his home county of Carlow, up to his neck in drilling and ambushing in the C Company of the IRA, where his family had their farm in Tombeagh since the 1700s.

One interesting thing about the Barrys’ ancestry is that, according to Kevin Barry’s Rathvilly school master Edward O’Toole, the Barrys were descended from the Normans. Gerald Barry (1146–1223), seems to to have been the common ancestor of the Barrys in Ireland. (Edward O’Toole, Whist for your life, that’s treason – Recollections of a Long Life, Dublin: Ashfield Press, 2003, p. 140)

Geraldus de Barri (Geraldus Cambrensis), was the first recorded Barry to arrive on Irish soil. He came to Ireland as a tutor to the sulky young King John in 1185. He thought of Ireland as a land of idle louts and said, ‘The men were as bad as their masters, devoted to Venus and Bacchus.’ In his Topographica Hiberniae, he observed of the Irish their strange flowing beards and odd clothes and that they were far too in love with leisure, yet he appreciated their ‘commendable diligence [only] on musical instruments, on which they are incomparably more skilled than any nation I have seen’. (The Project Gutenberg e-book of Ireland under the Tudors, Volume I (of II), Ireland under the Tudors, by Richard Bagwell)

Geraldus, then, was the unlikely progenitor of one of the most infamous Irish martyrs of the independence movement. Tutor to the Anglo-Norman Plantagenet king who was handed the task of colonising Ériu by his father Henry II, he was certainly an unlikely ancestor for a Republican martyr. But there it is.

Anyway, fast forward to the first quarter of the twentieth century in Tombeagh, where the Barrys kept their dairy farm (and had expanded to a Dublin premesis and dairy yard in 1905). Kevin was a medical student at UCD, most distracted by his activities in the IRA, being a passionate Republican since he was 15 years old.

In the summer of 1920, after a few successful ambushes in Dublin that yielded the boons the Volunteers needed without any casualties at all, Kevin was busy in his home county of Carlow, up to his neck in drilling and ambushing in the C Company of the IRA, where his family had their farm in Tombeagh since the 1700s.

At the end of a letter to his school friend at Belvedere, Leo Doyle, he describes the political situation around Carlow:

‘There’s hell around here. 30 houses raided, 2 men arrested, 1 wounded and about 40 men “sleeping out”. There are 6 men arrested in Baltinglass and 30 more lorries have arrived from the Union from the Curragh [in Kildare, a military base].’

He signs off again with, ‘Yours till I’m qualified (ad saecula saeculorum), Kevin.’

By Kind permission of the Kevin Barry estate

Kevin was, that summer supposed to have been preparing (or not) for the resits of his medical examinations at UCD, which he had failed in May that year. 1920.

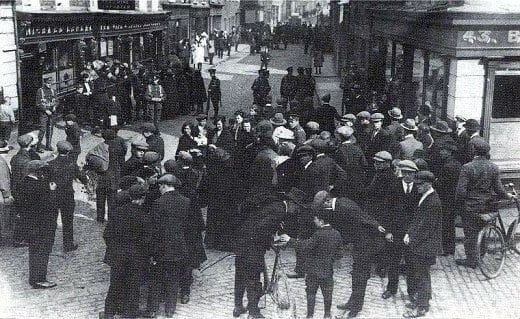

Pádraig Ó Catháin, Adjutant of the Carlow Brigade, described Carlow in 1920 as ‘a difficult year’. Raids, arrests and sentences depleted company, battalion and brigade staffs.

‘The house of a Volunteer was burned at Clonmore, … two shops that Volunteers worked in were burned in Tullow following an ambush in which two police were killed, and two Volunteers were killed at Barrowhouse in a badly sited ambush. A clinician alleged to be consorting with the Tans was shot dead in Borris and a Tan was badly wounded outside the Barracks.’

As if this wasn’t enough, some of the Carlow Volunteers conscientiously objected to some military orders so that the Volunteers lost their Intelligence Officer (Conkling), the Quartermaster (P. O’Toole) and the Adjutant. But it was intelligence work that was emphasised then, with the aim of capturing documents.

‘The police went from plain capers to figures in an effort to evade us, but they determined ‘exact times and areas of the night Lancia car patrols which they sent out.’

Raids and ambushes were continually plotted and carried out due to the need to acquire ammunition, of which there was a shortage and so, overall, there were no large-scale military attacks in Carlow in 1920. It would change in 1921 when the Volunteer forces were more organised and attacks were made at Bagenalstown Barracks and on concentrations of Black and Tans in Carlow, Tullow and Borris, but only when they could determine the points at which the British presence was most vulnerable.

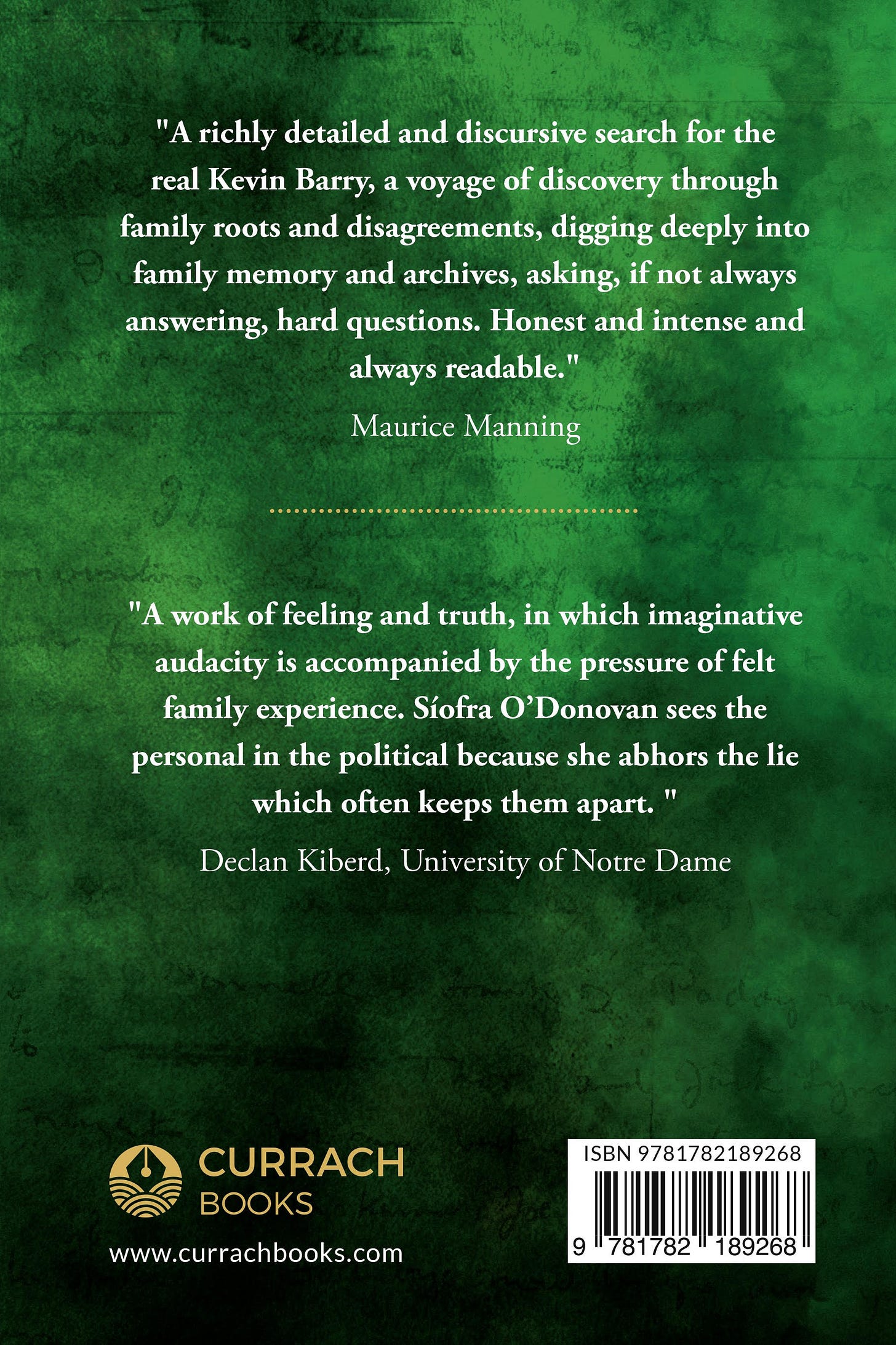

If you would like to buy a signed copy of Yours Til Hell Freezes, please PM me. Thank you. To read more about it, see here. and here.

It was on orders from the Active Service Unit, spearheaded by Michael Collins, that the Carlow C Company were to burn down Aughavanagh Barracks.

It was a wild, wet night in July 1920. Matt Cullen, Kevin and Michael Barry and the others came to barracks at Aghavannagh on a fleet of bicycles. Kevin was the leader, he broke in through a back window and was confronted by the housekeeper forcibly when Kevin told her they were going to burn down the barracks. She gave him powerful verbal opposition and she was an able dealer. I don’t know her name but she was well able to hold her corner. The lads stopped and thought about what they were about to do. And whatever she said to them, they agreed not to do it.

(Interview with Con Foley at his home in Knockananna, County Wicklow, July 2019. © Siofra O’Donovan)

I found out about the housekeeper from an old man called Con Foley, whom I interviewed in July 2019.

Apart from all of this war on the roads and ditches of Ireland, there was still time for merriment. At Tombeagh, many songs were sung by the fire. Kevin used to sing this cattle-driving song written by Percy French in 1910, set to the air of an older Irish song. It’s also about a tricky encounter between an old couple with their cattle and two RIC policeman, Flynn and Kilray.

Well, when they brought back the cow says the Widda ‘Ochone!

How I wish them police would leave people alone.

For if I could have proved the oul’ reptile was drowned

I’d ha’got compinsation – aye – nine or ten pound’.

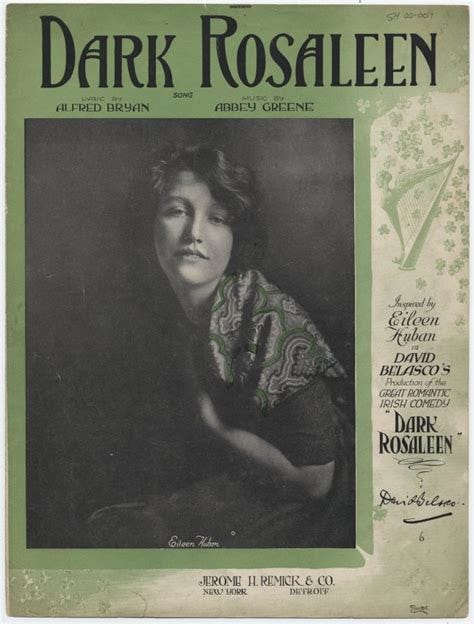

Kevin seems to have loved Percy French songs and it’s not hard to imagine him singing loudly at a gathering in Tombeagh, surrounded by friends and family. ‘He [Kevin] was the heart of the party. His brother Mick used to sing “Róisín Dubh”.’

Kevin’s older brother Michael was more reserved, and a song like ‘Róisín Dubh’, ostensibly a romantic lament, was more in tune with his demeanour. Also known as ‘Dark Rosaleen’, the song dated from the sixteenth century – it was a political song camouflaged as a lament. Nationalism, throughout the nineteenth century in Ireland, cast the lamenting woman, Dark Rosaleen or Caitlín Ní hUallacháin, as the symbol for their lost country.

In the turmoil of land reclamation and rebellion, songs (of a rebellious nature) released the angst of the struggle for freedom and brought people together in a way that we can’t even imagine today. It’s not, however, as if everyone was at home singing rebel songs in rural (nor urban) Ireland in the lull between rebellions. The mechanics of rebellion were brutally demanding.

But apart from singing, there was storytelling, still a rich tradition in Ireland, and often narrated by seanchaí. This tradition was still very much alive in Ireland at the time. My father gave me a tattered volume of folk tales written down by Seumus MacManus, one of the last great seanchaí. This book, well thumbed and unravelling along its spine, is inscribed in the frontispiece in pencil, in Kitby Barry’s handwriting:

Kathy and Sheela Barry, Tombeagh, Hacketstown, Co. Carlow

The book, whose title and publication date have disappeared due to its condition , contains old Irish folk tales like Billy Beg and the Bull, Murroghoo-More and the Murroghoo-Beg, Shan Ban and Ned Flynn, The Black Bull and the Old Hag of the Forest – full of old Irish pastoral storytelling motifs of shapeshifting animals, giants, crafty old magic-wielding witches, ungrateful daughters who got thrashings from their mothers with ‘a good stout sally rod’ – saved, of course, by a king’s son. The book may be a copy of In Chimney Corners: Merry Tales of Irish Folk‐lore, published in 1904 by McClure, Phillips & Co. in New York, but the book is so worn it is impossible to tell.

Kitby, Shel and their mother, sitting with Nana Dowling, the grandmother, would read these stories in the evenings to each other and to the younger children, so it is entirely possible that Kevin would have heard them by the fire at night in Tombeagh. McManus tells us:

These tales were made not for reading, but for telling. They were made and told for the passing of long nights, for the shortening of weary journeys, for entertaining of traveller-guests, for brightening of cabin hearths. Be not content with reading them …

In those days, Tombeagh was dimly lit with gas lamps. Kevin Barry’s maternal grandmother, Nana Dowling, had been living in Tombeagh since 1908, when Tom Barry, Kevin’s father, had died. Her own husband, James Dowling, had died the year before and Kitby and Shel thought it was better for Nana Dowling to be installed at Tombeagh, rather than stay at her own empty home in Drumguin, the neighboring townland. Nana Dowling would always have been there when Kevin came down from Dublin in the summers, after he started secondary school in 1913.

Nana Dowling, in her later years, would rarely have come down from her upstairs room. There are many stories surrounding her, but there are a lot of stories at Tombeagh that intrigued me as a child. There was the one about ‘a headless horseman [that] used to come down the lane’, and the one about the ghost of that first Kevin Barry who died at sea, coming home from New York seen, as my father told me, at Tombeagh, ‘in the dusk of a summer evening’.

Kevin Barry Jr. was told about a curious funeral, as a child:

‘My mother’s father went up the road for a walk and saw a funeral at the bend in the road … he saw the horses and traps … there was no funeral that day … it was a ghost funeral.’

I loved the old stories from Tombeagh as a child. My father and my aunt Sheila told me the story of Nana Dowling meeting an old woman at the bridge when she was out with her pony and trap, going to the village. The woman came out from behind the bridge, and asked Nana to get her a pound of bacon on credit from the butcher. She told her her name. Nana Dowling told this to the butcher, who asked her for a description of this woman, and, on hearing it, he declared that she had been dead for ten years.

There were great bouts of drinking too…especially in that last summer of Kevin Barry’s life. He and Pat Gorman would drink in Richardson’s Hotel by Glendalough Lake, preferring it to the Royal Hotel, which was full of Dubliners. These day-jaunts became longer than a day. Kevin refers to a friend from Coolmana near Tombeagh who was ostensibly a week late for his dinner. Kevin’s letter to Bapty Maher shows just how much fun they all had that summer.

It was a bloody pity you didn’t come yesterday. We had a good day [so good] that my ruddy head is singing like a top and my eyes are all bloodshot. I got rid of Mike and spent the day with Gorman, but I’ll never touch a drop again as long as I live. We stopped in Tinahely, Aughrim, Woodenbridge, Avoca, Rathdrum and Laragh going and ditto coming back. I wasn’t in the Bed or anywhere else. I was laying on the sofa in Royal Hotel [Glendalough] with a Belgian girl drinking. We held up the car for 1½ hours while they were looking for us and we made them stop in Rathdrum one hour, Woodenbridge ½ hour and Aughrim 1½ hours so it was 1.30 before we got to Hacketstown. We had to lift Gorman out of the car and carry him home. He was absolutely rotting. I fell off the bike twice on the way home and I was up all night drinking water. Damn booze anyway.

Yours till I’m qualified K.G.B.

He goes on to mention Peg Scully, who told him that he made a speech about Medicals and Gorman made one about Clerical Students. He said he was ‘f——-d’ if he remembered. Regarding the same drinking expedition, he wrote to his school friend Leo Doyle. In this letter, he apologises for not greeting him in Hacketstown with Fr Dunne…

‘but as I was drilling a company of rebels I didn’t like to speak to you as Fr Matt might not be pleased.’

Fr Matthew Dunne was a friend of the Doyles and the Barrys – the problem was that he was a Chaplain in the British Army. This letter is also full of drinking bravado, and had another reference to Pat O’Gorman having to be lifted out of the car.

‘I also met two university girls, but there was a dud crowd down from Dublin.’ Kevin states that he will be up in Dublin in about a week and I’ll see you some evening outside the old College … ’

The letter would have been written in late August 1920.

Maybe the only person who knew Kevin was going to die in 1920 before he was even arrested for the ambush at Monk’s Bakery was Eileen Dixon, a close friend of the Barrys. She lived in Sandycove and would spend evenings in the Barry drawing room in Fleet Street. Part of their entertainment would come from Eileen’s ability to read tea leaves and palms. One evening in 1920, she took Kevin’s palm. She stopped, and looked up at him.

‘You should be dead,’ she said. The story of her reading of Kevin’s hand was one that gripped me as a child. I could see Kevin in the sitting room in 8 Fleet Street, bemused when Eileen Dixon told him he was going to die. He just didn’t mind, I was sure of it. Eileen was known to the Barrys as Chimo, and before she went on to become a doctor, she dabbled in a bit of palmistry.

We don’t know how anyone in Kevin’s family reacted to this shameless but accurate prediction. Kevin’s life line on his palm was extremely short, and Eileen had never seen one this short before. We can imagine, from the tone of Kevin’s letters and from his ability to compartmentalise his life, that he would have laughed it off. Perhaps Kitby, his sister, who knew the extent of his involvement in the War of Independence, would have felt an ominous shiver if she’d been in the room. I am fairly certain that this was around the time that Kevin had come back up from Tombeagh to sit his repeat exams at UCD. He would be dead by 8am on 1st November, 1920. Today is his 104th Anniversary. I’d like to honour also my cousin Kevin Barry Junior who passed away last December 2023. RIP.

If you would like to buy a signed copy of Yours Til Hell Freezes, please PM me. Thank you. To read more about it, see here. and here. Or you can…

©Siofra O’Donovan, Yours Til Hell Freezes, 2020

If you would like to buy a signed copy of Yours Til Hell Freezes, please PM me. Thank you. To read more about it, see here. and here.

Like some, I have on both sides of my family, strong links to the Nationalist cause and to subsequently what became known as the Republican Movement. Kevin Barry's story is heart-breaking. And it is even more heartbreaking to think of what is being done to our sacred land by the mediocre but ambitious sell outs who are bent on destroying us on behalf of the latest shower of feudalists (aka, globalists). I do wonder, however, were we ever really free? I don't think so. I love you, Jim (RIP).

Excellent blog, I learned more facinating and intimate insights about your ancestors, and more gaps are filled regarding Irish history, thank you.