The Ogre is a funny one. We know a sugar-coated, sterilised version of him in Shrek, an Ogre has none of the habits of a real Ogre, although he does live alone in a swamp in the middle of a Dark Forest. (in DreamWorks’ movie, he says that babies are like muffins to ogres). People fear only his appearance: he resembles an Ogre, but in fact he is not an ogre at all. He also has emotional sensitivity. Unheard of in Ogres!

The message of the Shrek story is not to pay too much attention to appearances. So the ugly, kind-hearted one remains isolated in the Dark Forest, like the Beast in Beauty and the Beast. The princess Fiona in Shrek has a public and private side: she is beautiful during the day but hideously ugly at night, and her dream-prince is vain, selfish, and unbearable. She is like an Ogre-, but like Melusine who was cursed to take the form of a mermaid-ogress on Saturdays). The king is in his position only through his wife’s love and kiss, as he himself is just a frog, and so on. She is a shape-shifting Ogress. More on Ogresses later.

Origin of the word Ogre

The origin of the word “ogre” is uncertain. It may derive from the name of the Roman mythological god of the underworld, Orcus. Or it could be linked to the word for Hungarian- stemming from the devastation caused by Hungarians in the Middle Ages.

It’s also possible that the 12th writer Chrétien de Troyes wove the legend of Lancelot as political propaganda during the marriage of the French Queen Margaret and the Hungarian king Béla III. In this narrative, Lancelot is an implicit reference to the Hungarian king László, aiming to impress visiting Hungarian dignitaries. So, the word “ogre” could be connected to political intrigue and mythical storytelling rather than to the Hungarians themselves.

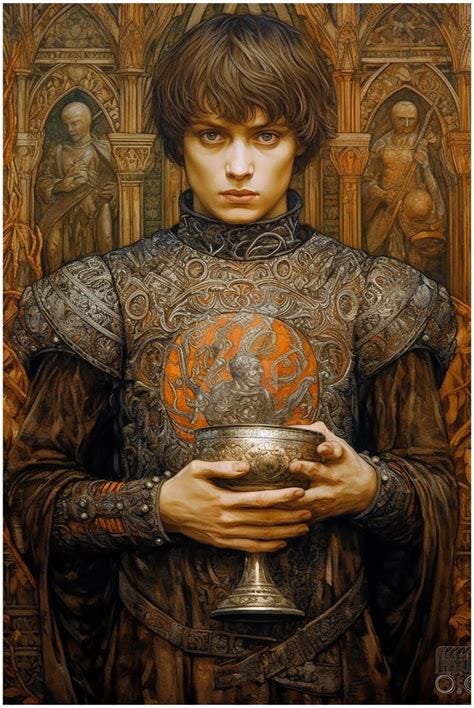

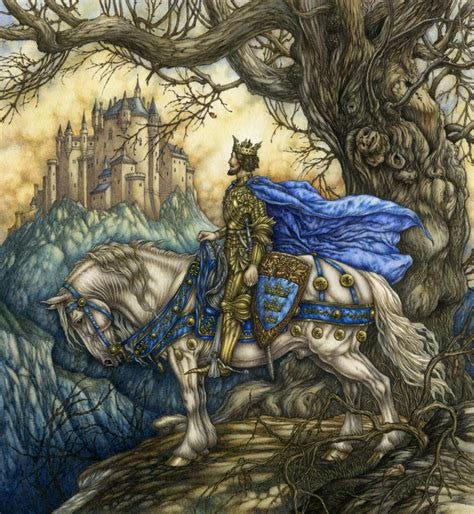

The oldest known occurrence of the word in literature is in Chrétien de Troyes’ work “Perceval, the Story of the Grail” (Fr. Perceval ou le Conte du Graal). Perceval is the Grail Knight, who seeks to restore the Grail to the Fisher King whose Kingdom has become a Wasteland. Chrétien’s work mentions a prophecy that the kingdom of Loegria, [which was once the land of Ogres], will be defeated by a spear. [The legendary kingdom of Loegria is a variation of the names Lloegr or Lloyer, which are Bretonic and Welsh names used in the Arthurian legend for England.] The name is not etymologically related to the word “ogre,” but Chrétien de Troyes juxtaposes the words, exploiting their mutual rhyming.

The poem likely contains a reference to two earlier literary works: Bishop Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae and the Norman poet Wace’s Roman de Brut. The latter presents, in Anglo-Norman, the mythical history of England, stating that before the arrival of Brutus, the Trojan ancestor of the Britons, the land was inhabited by giants! However, Armel Diverres has pointed out that Wace used the term gaians (giants) to refer to the inhabitants of this ancient kingdom, never the word ogre.

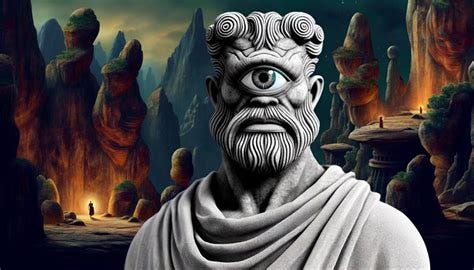

The Aarne–Thompson classification system, which lists folklore motifs, widely recognizes the plot pattern known as the “blinded ogre” (number 1137), which is prevalent worldwide. The earliest known version of this is in Homer’s Odyssey, where the hero Odysseus blindsthe Cyclops Polyphemus.

In French, the word Ogre featured in Charles Perrault’s fairy tale collection Tales of Mother Goose, (1697). The author himself defined the word in a note related to one of the tales as follows: A wild man who eats little children. The following year, Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy used the word in her poem The Orange Tree and the Bee.

The corresponding term in Italian is orco. The earliest known occurrence of the word in literature is in Jacomo Tolomei’s work “orco... mangia li garzone” (“ogre... who eats the boy”) from 1290. In Ludovico Ariosto’s epic “Orlando Furioso” (1516), in the 17th song, the “orco” is depicted as a predatory and blind monster, possibly influenced by the story of Polyphemus the Cyclops from the Odyssey.

The word “orco” also appears in the name of an Etruscan ancient tomb in the Montterossi necropolis. Giambattista Basile (1575–1632) used the Neapolitan form of the word, uerco, in his work Pentamerone (tale no. I-1).

Ogres in folklore, fairy tales, and mythology

Ogres are described as beastly, coarse, dim-witted giants. In Breton folklore, ogres are considered builders of megaliths and dolmens, but the character became more widely known through Charles Perrault’s fairy tale collection Tales of Mother Goose:

One of the most famous ogres appears in the tale Tom Thumb (French: Le Petit Poucet).

Perrault also used the word ogre for the character in Puss in Boots (French: Le chat botté), although there is no direct reference in the tale to the character eating humans. This giant, like the Greek mythological figure Proteus, had the ability to transform into any form. Puss in Boots ate him after he transformed into a mouse.

Ogres are wealthy. And they have many talents, like the ogre in Thumbelina move from one place to another with his seven-league boots, while the ogre in Puss in Boots can change shape.

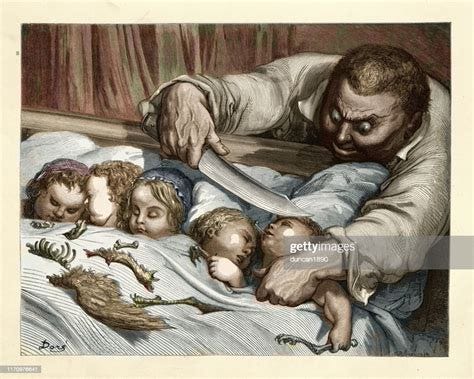

But their obssession is to eat fresh meat, preferably that of children. Like the Witch in Hansel and Gretel. Unlike the wolves in fairy tales, who eat their victims raw, ogres prefer to eat meat prepared and cooked with sauce, similar to how veal or lamb is prepared for consumption.

Yet Ogres have many friends. Think of Shrek! In the tale of Thumbelina, the Ogre shares fresh meat with his friends. He is a “good husband” and a father of seven daughters, whom he raised like princesses. But he loses his power when his seven-league boots are taken away from him while he sleeps.

In Thomas Malory’s work “Le Morte d’Arthur,” an ogre kidnaps the Countess of Brittany. The ogre also forces the women he kidnaps to work as cooks when roasting small children over a fire.

THE OGRESSE!

In French, the feminine form of the word ogre is ogresse, which refers to a similar female character. The Finnish equivalent of the word is “syöjätär” (literally “eater lady”).

Sleeping Beauty

An Ogresse appears in Perrault’s version of the tale Sleeping Beauty (French: La Belle au Bois Dormant), in its lesser-known ending, which is not included in the Grimm Brothers’ version of the tale or in Disney’s version. In Perrault’s tale, the ogresse is the queen and the prince’s mother wakes Sleeping Beauty from her hundred-year slumber. [ As in Maleficient, the Disney movie] Initially, she seems almost normal but arouses suspicion and even scares the prince, although he loves her. This is because she is related to giants, and rumors at court suggest that whenever she sees small children, she finds it “difficult to restrain herself from attacking them.” !!

They tried to keep it hidden from her that her son and his new spouse, Sleeping Beauty, had had two children, a daughter named Aurora and a son named Day.

When the wicked queen, their grandmother, finds out about the existence of the children, Aurora is four and Day is three years old. She wants nothing more than to devour them, orders her butler to slaughter them, first Aurora and a week later, Day, and gives instructions on how they should be prepared as food. [typical Ogre-some behaviour] The butler refuses to obey and takes the children to a hiding place, slaughtering a lamb instead for the Queen’s meal [like the Huntsman in Snow White who kills a wild animal and takes its heart to give the Evil Queen to eat. ]

The queen in Sleeping Beauty believes she has eaten her grandchildren. She then asks the servant to slaughter Sleeping Beauty herself but the servant confesses to the wicked queen what he has done. When the Queen learns the deception- she orders a pot brought to the palace, filled with snakes and other dangerous little animals. In the absence of the prince, she plans to throw Sleeping Beauty with both her children and the servant into it. However, when the prince returns home earlier than expected, he asks in horror what is happening. The frightened queen jumps into the pot herself and meets her death. Sleeping Beauty and her children are saved.

So, quite a different version of Sleeping Beauty. Prince Charming does not come into it, in terms of saving her. In the Grimm version, however, perfect balance and harmony is achieved in the Princess being awoken by the Prince.

“She opened her eyes, awoke, looked a thing in friendship. They came down the stairs, and the king awoke and the queen and the entirely courtly estate, and all looked at each other with big eyes. And the horses in the court stood up and shook themselves: the hunting dogs jumped and wagged their tails; the pigeons on the roof drew their little heads out from under their Wings, looked around, and flew across the field: the flies on the wall asked again: the fire in the kitchen brightened, flickered, and looked the dinner: the roast began again to sizzle: and the cook gave the scullery boy a box in the ear that made him yell: and the maid finished plucking the chicken.” - Sleeping Beauty, The Brothers Grimm

Perfect order is restored in the Kingdom. No sign of the Queen trying to eat her children. All is as it should be in a happy Kingdom.

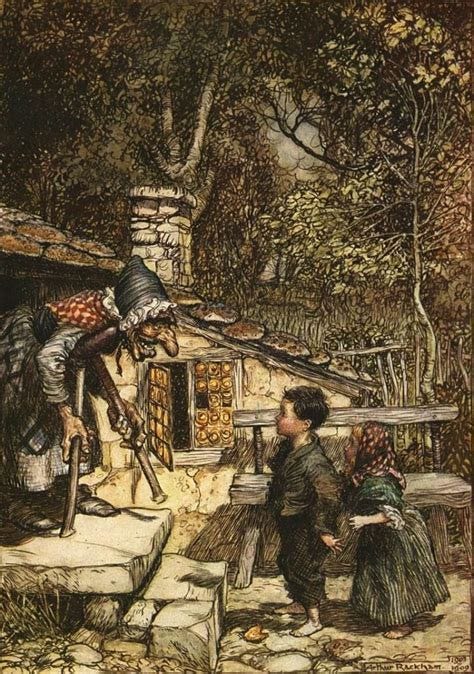

Hansel and Gretel

In Grimm’s fairy tale Hansel and Gretel, after getting lost in the woods, Hansel and Gretel discover a house made of bread and gingerbread, inhabited by a woman referred to as a witch in the tale. She wanted to fatten Hansel up to eat him and use Gretel as a servant. However, in the end, Gretel pushes her into the oven, where she had lit a fire to bake Hansel. Afterward, they return home by a different route, crossing the lake on the back of a duck, and they also carry with them pearls and jewels they found in the witch’s house.

Characteristics of Ogres

In Perrault’s tales, only three ogres appear—two male and one female. In all cases, they are wealthy and hold high social positions: The ogre in Thumbelina owns a large amount of gold and silver, which Thumbelina and her brothers eventually acquire;The ogre in Puss in Boots is a luxurious lord living in opulence and owning extensive land;The ogresse in Sleeping Beauty is a queen.

Reading/ Listening:

The Feathered Ogre by (edition) and Tabagnino the Hunchback (edition) Italian Folktales retold by Italo Calvino, Recorded by me:

Giamatista Batale - Verde Prato

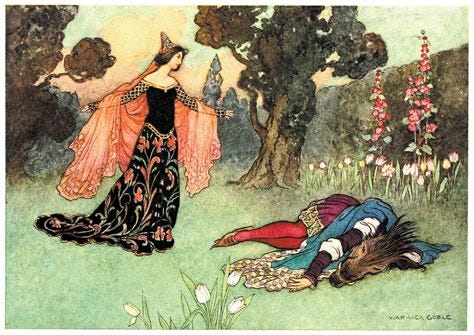

The Three Sisters or Green Meadow (Italian: Verde Prato) is an Italian literary fairy tale written by Giambattista Batale in his 1634 work, the Pentamerone. It tells the story of a maiden having secret encounters with a prince with the use of magic, him almost losing his life and her having to search for a cure for him.

A woman had three daughters; the two older were very unlucky but the youngest, Nella, was very fortunate. A prince married her and hid her from his wicked mother, visiting her in secret. She could throw a powder in a fire, and he would come to her on a crystal road. Her sisters discovered this and broke the road, so that the prince was injured when he was coming to her.

He was dying. His father proclaimed that whoever cured him would marry him, if female, or have half the kingdom, if male.

-Verde Prato, The Green Meadow, Gimbatista Batale

Symbolic Meaning

Psychoanalytic interpretations of ogre characters. An Ogre can be interpreted as a nightmarish father figure, embodying domestic violence and the fear evoked in children.

Bruno Bettelheim in “The Uses of Enchantment” maintains that the ogre represents early childhood fears in child’s fears which Freud called ‘the oral stage’, an age of a destructive nature. According to him, the ogre symbolizes this specific desire and the victory over the ogre metaphorically represents overcoming this desire. I don’t personally subscribe to this interpretation. Children are innocent and exploring the world. An ogre knows the world, has retreated from it, and eats innocent children in revenge!

Beauty and the Beast

Beauty and the Beast was originally written by French novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve (ca, 1740 in La Jeune Américaine et les contes marins -The Young American and Marine Tales).

Later, Andrew Lang retold the story in Blue Fairy Book, a part of the Fairy Book series, in 1889. The fairy-tale was influenced by the story of Petrus Gonsalvus as well as "Cupid and Psyche" from The Golden Ass, written by Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis in the second century AD, and "The Pig King", an Italian fairy-tale published by Giovanni Francesco Straparola in The Facetious Nights of Straparola around 1550.

This Beast differs from other Ogres. He has something to offer Beauty, whose moral compass is in tact. Once transformed, he is all valour and beauty himself.

The two may seem to one alike- the Beast may offer creativity, but the Demon Lover will suck the creativity away and kill us. The Beast is able to let the woman Abe free; he allowed her to choose. He does not try to make her into his own image, as does Dracula, who turns his women into vampires like himself, feeds on their life energy, and makes them his slaves. IN living with the Beast, love, generosity, creative vitality, spiritual radiance are felt and shared. THe Beast offers the elixir of life, while the demon lover feeds off one’senergy and leaves one to the living death of the ‘Undead.’

P. 183-4, On the Way to the Wedding, by Linda Schiese Leanord

‘Writing the story of Beauty and the Beast brought me into the heart of the forest and deeply into the forest of my own heart. Like Beauty, I had to take the journey into the forest to the the Beast’s palace to redeem my inner father, whose beautiful Beast was bewitched , and to free the primal princely potency, to the find the instinctual man of heart in myself. ... I found a new centre , a rose centre, a bud that could open its pearls and begin to receive the warmth of love..“ Linda Leonard.

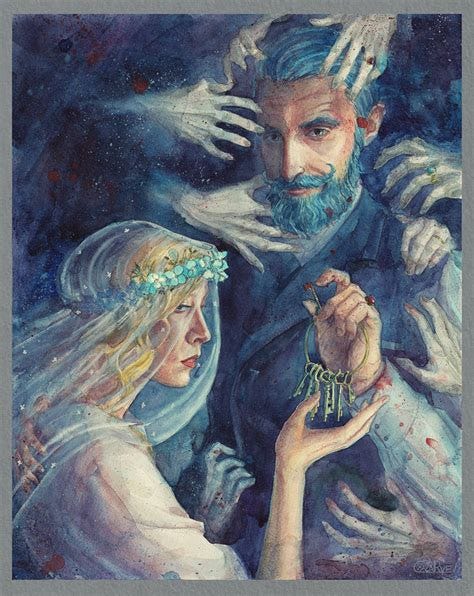

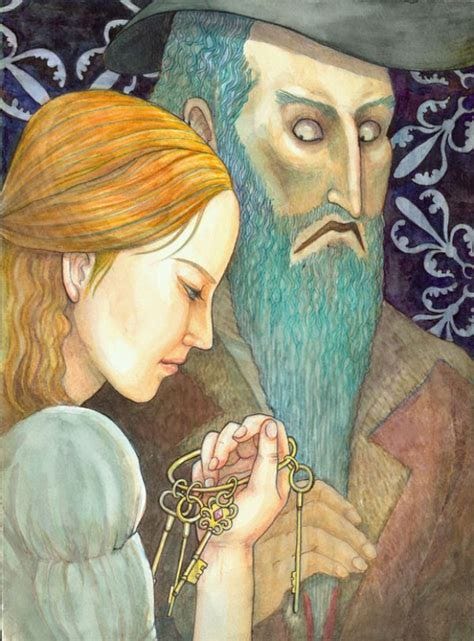

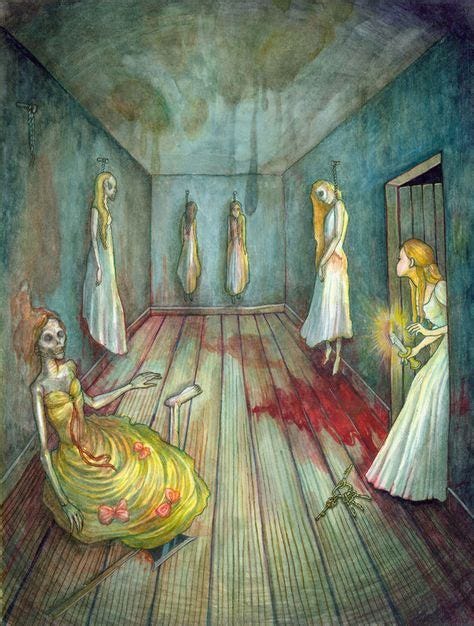

The Tale of Bluebeard by Perrault

(The Psychopathic Ogre)

Once upon a time, in the fair land of France, there lived a very powerful lord, the owner of estates, farms and a great splendid castle, and his name was Bluebeard. This wasn’t his real name, it was a nickname, due to the fact he had a long shaggy black beard with glints of blue in it. He was very handsome and charming, but, if the truth be told, there was something about him that made you feel respect, and a little uneasy...

You can listen to my recording of Bluebeard as written by Clarrissa Pinkola Estes here

Bluebeard often went away to war, and when he did, he left his wife in charge of the castle. He had had lots of wives, all young, pretty and noble. As bad luck would have it, one after the other, they had all died, and so the noble lord was forever getting married again.

“Sire,” someone would ask now and again, “what did your wives die of?”

“Hah, my friend,” Bluebeard would reply, “one died of smallpox, one of a hidden sickness, another of a high fever, another of a terrible infection... Ah, I’m very unlucky, and they’re unlucky too! They’re all buried in the castle chapel,” he added. Nobody found anything strange about that. Nor did the sweet and beautiful young girl that Bluebeard took as a wife think it strange either.

She went to the castle accompanied by her sister Anna, who said:

“Oh, aren’t you lucky marrying a lord like Bluebeard?”

“He really is very nice, and when you’re close, his beard doesn’t look as blue as folk say!” said the bride, and the two sisters giggled delightedly. Poor souls! They had no idea what lay in store for them! It was this: you can listen to the story here;

Developing a relationship with the wildish nature is an essential part of the women’s individuation... she must go into the dark, but at the same time she must not be irreparably trapped, captured, or killed on her way there or back.. Bluebeard is about that captor, the dark man who inhabits all women’s psyches, the innate predator.. He is a specific and incontrovertible force which must be memorised and restrained. To restrain the natural predator of the psyche it is necessary for women to remain in possession of all their instinctual powers. Some of these are insight, intuition, endurance, tenacious loving, keen sensing, far vision, acute hearing, singing over the dead, intuitive

healing, and tending to their own creative fires .. P 44, Pinkola Estes, THE NATURAL PREDATOR OF THE PSYCHE [Clarissa Pinkola Estes, Women who Run with the Wolves

Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber gives us a first person narrated richly told long short story that gives sinister insight into the kind of psychopathic ogre we are dealing with. I read the. first ten pages of the story here…

Ferocious, savage, intentional destruction of innocence is the life-blood of the Ogre, and Carter puts it into exquisite prose… you can read the rest of it here.. https://archive.org/details/bloodychambero00cart

It is the brokenness, the desperate lonliness and the failed magician aspect of the ogre that we may recognise in ourselves. Delve into these tales, and see where they bring you…

I have often wondered abou this funny thing, the Ogre.

At once, Ogre seems to embody qualities from Fairie, pre-christian magical reality as well as a definite unhealthy abrahamic depravity.

It really appears then, that the Ogre is of a Medaevel origin, when French was still an imaginative language, Troubadours sang their praises to feminine beauty, and Cathars travelled the spheres.

Fascinating indeed.