Holy Island...

Visiting Exiles off Tuamgraney on a September Afternoon

We all leave one another. We die, we change - it's mostly change - we outgrow our best friends; but even if I do leave you, I will have passed on to you something of myself; you will be a different person because of knowing me; it's inescapable.- Edna O’Brien

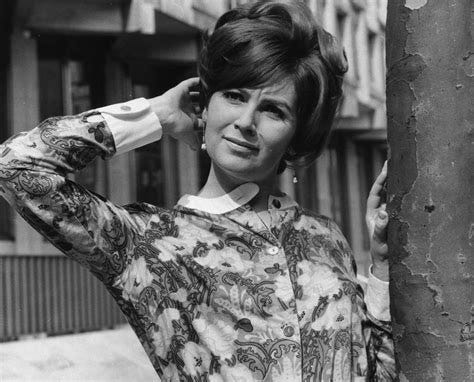

Last weekend I was tearing around Sligo and Mayo, and never caught up with myself until now to tell the tale of Holy island. We were told that the end of September was the last day we could ever take the boat over to Holy Island. Orla-Borla, a devoted fan of Edna O’Brien, whose grave has been there since August (Edna’s) wanted to make the pilgrimmage. So I came along.

It was a day with a decent amount of sunshine, but the clouds mostly kept it for themselves. The boatman was an ironic man who chuckled a good bit without revealing much about himself but he was great fun, as was his partner in crime who laughed heartily when we struggled with the odd-shaped, skimpy life jackets that did not look as if they could save us at all. On we went into the depths of Lough Dergh on a little blue boat.

Stepping off the boat, there was a murmuration in the sky, dancing across grey clouds. We stepped past an old oak tree with a double bough. It was saying something, though I did not know what.

Holy Island is a most Holy Island indeed. It is an island off an island- a sort of banishment in itself for Edna O’Brien. Inis Cealtra is scattered with the bones of very ancient churches and gravestones of saints. St Colum mac Cremthain founded a monastery here in the 7th Century with a large number of followers ‘at the bidding of an angel’. He founded a tree called Tilia, whose juice-distilling filled a vessel and that juice ‘had the flavor of honey and the headiness of wine.’ (James F. Kenny, The Sources for the Early History of Ireland: Vol. 1 New York 1929, p. 285).

There was a monk banished from Holy Island. Monks were, under the rule of Benedict, to spend a large part of the day in physical labour. But the first rule of Benedict was Obedience. In the early 11th Century, a monk called Anmchad entertained some guests with Corcan the Abbot’s permission. They asked for wine, and Anmchad pretended to the abbot it was for the altar. There was a feast and when the abbot found out, Anmchad was banished to Fulda in Germany, and died in 1053 as an inclusus, jailed up in a narrow cell. (Bartholomew MacCarthy, The Codex Palatino-Vaticanus, p. 31- Thanks to Gerard Madden’s Holy Island pamphlet)

The Vikings had a great time burning down the monastery in 922 but still, the island was occupied until the 13th Century. Brian Ború’s brother was at one point the Abbot of Inis Cealtra monastery. There are six ruined churches, a monastic cell, a cemetary with 80 graves. Edna O’Brien chose to be buried here and she is the last person that will ever be buried on Holy Island. A sort of self imposed exile, at a safe distance from the country from which she was banished.

Her funeral was unusual in that, in the very place that she was exiled from, she was celebrated by Celbrant Fr Donagh O’Meara in Tuamgraney as an “extraordinary woman” and “speaker of truth” who held up a mirror to Irish society. Well, some years ago her mother hid her first novel ‘Country Girls’ in the coal shed, for shame. Edna was banned in 1960 in a different kind of Ireland to the one we know now. (of course we are far from free from censorship, still. Helen Mac-an-Tee’s legislation is testament to this).

“We didn’t thank her for it. Like a lot of prophetesses of the past, we undermined her, we isolated her and rejected her message and she must have deeply felt that,” the priest-celebrant O’Meara went on, referring to her debut novel Country Girls that was banned and burned in East Clare in 1960. Now the whole country, including the priests, mourn. Her wish, at 93 years old. To return to her land at a but a distance. Being in it but not of it.

Censorship in Ireland was and is a very real thing. What was the ‘Committee on Evil Literature’? It was established by minister for justice Kevin O’Higgins in 1926. Ireland’s Censorship of Publications Board came into being in 1929, with it the power to ban any publication it deemed obscene. Priests ran it, along with William Magennis, a devout memboer of the Knights of St Columbanus who described Joyce’s Ulysses as ‘moral filth’ and Frank O’Connor as ‘a windbag with a nasty streak of malice’.

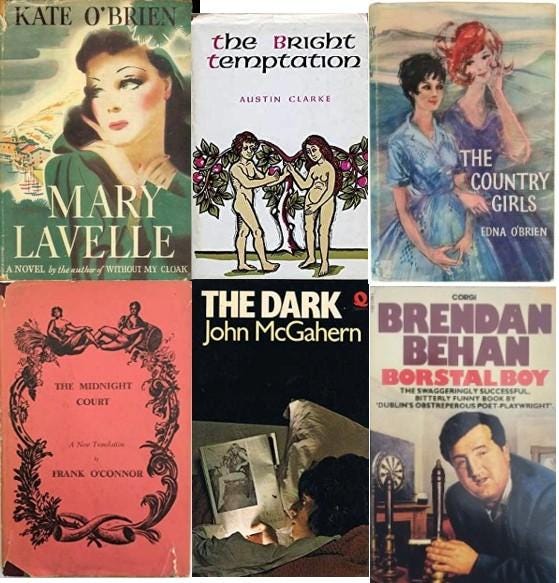

Aldous Huxley, Radclyffe Hall, Marie Stopes, John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingay, Graham Greene, F. Scott Fitzgerald, D.H. Lawrence, Somerset Maugham, Evelyn Waugh and Thomas Mann- all banned. Kate O’Brien’s Mary Lavelle (1936) and The land of spices (1941) were both banned on publication. Frank O’Connor’s English language translation of Brian Merriman’s Irish language work, The Midnight Court (1945) was appealed after being banned but they went on to ban four more of O’Connor’s books in teh 1940’s .

Time went on and they banned more books in the 1950s and 1960s, like J.P.Donleavy’s The Gingerman censored for obscenity- one of my favourite novels of all time. I read it as a teenager, and wondered what kind of a laundry a Magdalene Laundry was. Brendan Behan’s Borstal Boy was banned in 1958 until 1970 for no known reason. Then, there came Edna O’Brien, censored for her ‘smear on Irish womanhood’, disowned by her own mother- who hid her novel in the coal scuttle out the back. Five more of her books would be banned. The Country Girls was burned in East Clare in 1960.

The roof of the round tower was never completed because, they say, a witch cursed the stonemason who was building it. She made the stonemason angry, so he threw his hammer at her and when it hit her, she turned to stone. The standing stone of Inis Cealtra is the effigy of that Witch. That stonemason grew very ill and never completed the round tower.

Irish? In truth I would not want to be anything else. It is a state of mind as well as an actual country. It is being at odds withother nationalities, having quite different philosophy about pleasure, about punishment, about life, and about death. At least it does not leave one pusillanimous. - Edna O’Brien

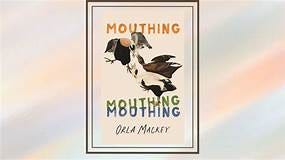

And finally, I’d like to introduce you to Orla Mackey’s novel ‘Mouthing’ that took a storm on this island and across the waters this summer. Published by Hamish Hamilton. Sharp, dark and brilliantly written this is a book you won’t regret reading for its insights into Irish rural life and humanity itself. Edna O’Brien would have been proud of one of her greatest fans.

Lovely sharing

❤️❤️❤️