Coming from the grey pallour of Ériu, Florence is a revelation of heat and a testimony to the power of the sun. Sol Invictus. We live here, under a constant lid of grey and lethal wind. It’s time to enact the power of the sun. Maybe we should do some kind of dance to beckon summer. I’d believed that the good weather on St. John’s Day boded well; we had a decent enough midsummer but we seem to be hurtling towards November at this rate. Nevertheless I jump in the sea and the odd lake just so that when I get out again the temperature feels mildly warmer than that cold Irish water. I’m certain for most of my life that I am living in the wrong country.

Decades ago I ran away with a friend or two, worked in Copenhagen for a summer - Burger King, flipping whoppers, where we earned a small fortune. Five Irish girls moved into a sublet collegium room in Amager (?) that belonged to a Zoology student so it had zebra rugs and tables and plants spilling all over it, and somehow five of us slept among and between the strange dead creatures and exotic plants. At the end of our summer at Burger King, me and the best friend took our well earned Whopper money and went to a millners where we had hats made, the trophies for our Burger King Trials. I got an estrachan pillbox hat made and my best friend a wide enough brimmed black felt hat made. Wearing her large rucksack on her back, she looked a bit like the snail from the Magic Roundabout. We went off on trains to Italy, the country of our dreams.

In Florence, we wandered through near empty streets, hoping to see some scene from A Room with a View, a Mr. Beeb or George Emerson or Lucy Honeychurch or her cousin (Maggie Smith) with a Baedaker guidebook, lost in the streets like ourselves, but that was another fantasy (just as my expectation of Florence was this time).

We stayed in an old Villa in Fiesole, where we were in dormitories, and were doled out spaghetti at dinner time from a giant pot. The receptionist was a man who we thought looked like Mussolini, who always wore an oversized, square-shaped blue jacket. He did the books and manned the one telephone in the Villa. My friend had to call home to get her leaving cert results, and when her father told her she got an ‘A’ in Art, she screamed, and her scream echoed in the dome of the fresco above us, and Mussolini was so angry he grabbed the phone from her and slammed it onto its holder.

“NO screaming.” said Mussolini, scowling, his hand firmly planted on the telefono.

The hostel-villa is long gone. I found no trace of it in Fiesole, which is now a Killiney-County-Dublin like enclave of closed gates with cameras, misering the panoramic views of Florence.

The empty, sleeply streets of a Florence I’d seen decades ago have vanished in the chaos of droves of crazed, exhausted tourists (11 million a year, I hear and of course I was one of them) slaving pathways to the Duomo with cameras, following their guides with flags. To survive a Florentine street is a feat, relieved by fleeing down backstreets to get away from the heaving, treacle-mass of folks with cameras. We realised we had walked straight into a trap. The Tour de France was hurtling through the city, so the carabinieri and all these virtue-signalling people in yellow Tour de France vests and the Polizi were having a field day with their railings, whistles and batons (the Polizi and the Carabinieri have fancy gloves). We had to flee even more and further to get away all that clatter and, of course the bicycles.

We thought the Santo Spirito area was a bit quieter like Kazimierz Jewish Quarter in Krakow, and then the bikes and railings were on top of us again on the Via Romano around the corner from the the B and B which was great though, a refuge near the Golden Theatre on Via Maria, from all of it and I promised to give them a plug. And the Chiesa Santo Spirito with its whole pile of Saints’ relics, most of them thigh-bones, encased in glass and gold. I’ve never seen so many human thighbones in one place. But at least there were no bicycles.

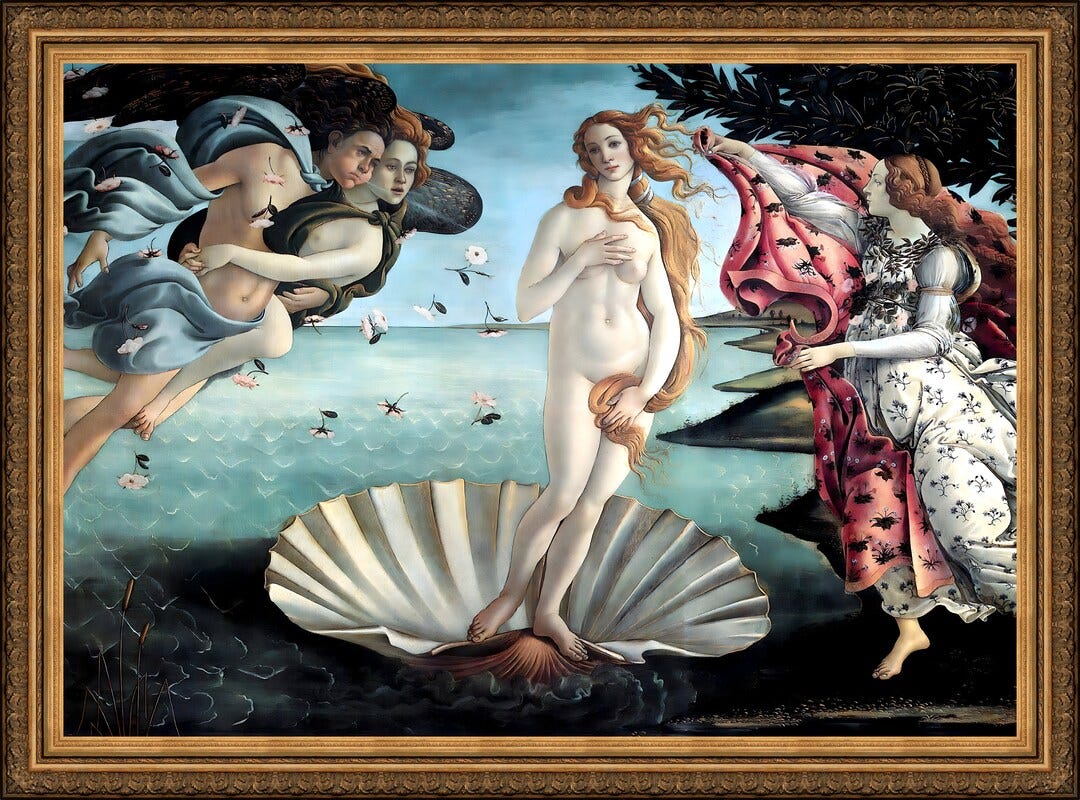

The man in the Fondazione Zeferelli said he was horrified by what has happened to Florence. Anyway the Uffizi galleries had to be visited. When I went to the Uffizi with my friend in our hats all those years ago, we walked in backwards through the Uffizi exit door, and nobody noticed. It was a habit of ours, walking in backwards through exits, a great way to get a free ticket into a gallery or museum. We said we’d write The Scabbers’ Guide to Italy. We never paid for the vaparetto ferries in Venice, either. I think we’d run out of our Burger King wages. When we found the Primavera by Botticcelli, which was our dream to see with our own eyes, my friend cried. These days, however, to even enter the Uffizi you had to hurl all your belongings into trays for security inspections, then wade on through the crowds- this was the first 8am slot, booked well in advance. Again, at least there were no bicycles.

View of Duomo from Uffizi

At the Primavera, there was a Chinese tourist alone, taking selfies at the painting, repeating ‘Cheese’ to herself, over and over again. I guess she must have been in love with the painting (or herself). The Primavera is one of the few non Christian paintings in a sea of Madonna and Child icons and paintings in the Uffizi. Botticelli used a lot of gold leaf to enchance his paintings.

Gold leaf gave an otherwordly quality to the art, and Botticelli used it to enhance his Madonnas, as they were set mostly in dim churches by candlight. That way, the image would flicker and that magical, otherworldly dimension was important for his audiences. He also used gold in the Primavera, in wings and tree trunks. Unless you see it with your own eyes, it won’t be that obvious. Simonetta, his model (she’s everything from Madonna to Venus) was always decorated with gold.

It’s all about the gold and the sun. Remedies, for me at least, for silvery grey gloom in Ériu. We need Lugh, or somebody to bring back the sun. What if it goes on and on like this forever, and Ireland is eternally Hibernia, the country of wintery cool mist and rain? Long ago the monks used to have vineyards in the monasteries in Ireland. I can’t imagine a grape surviving an Irish summer now. I said to my dear friend Magdalena with whom I was in Florence, that I was heading back into freezing cold weather and an eternal lid of clouds. She dreaded returning to ferocious heat of Krakow, which seems to be a sister city of Florence, in heat and sun and in dimension and beauty which brings the slaves in droves from all corncers of the world too, for Krakow is as tourist weary as Florence, it seems.

Botticcelli, patronised by the Medicis, was on his way to becoming a very famous artist (he could never have known how many tourists would snap his paintings 500 years into the future) and yet, he fell under the sway of a Domenican friar named Savonarola, who preached in Florence from 1484 to 1498, a wildly austere fire and brimestone extremist who exposed Medici corruption and had them driven out of the city into exile. So, Botticcelli, the painter of angels and pagan goddesses, fell under his sway. Botticcelli had painted his mythological, Neoplatonist Primavera as a wedding present for Lorenzo de Medici. Neoplatonism involved the quest for ideal forms of earthly and divine beauty, which was not necessarily religious at all.

Savoronola preached the dangers of pleasure. This ‘Venus’ (above) painted by Lorenzo di Credi in 1490, was the last Credi would paint like this. It is drawing from the Greek Classical world, particularly from the Greek sculptor Praxiteles- a perfect example of Renaissance art drawing from the source of the Classical, pagan world. Credi and Botticcelli and many other artists would burn many of their own works in the Savoronola-frenzy, much like cancel-culture, today. Gangs of children would invade houses in Florence, seizing mirrors, paintings and musical instruments and burning them in the Bonfire of Vanities. Fra Giramolo Savoronola had many classically inspired paintings and sculptures destroyed by urging Florentines to burn images of naked, beautiful women due to the perils of temptation. He may be responsible for the destruction of some of Florence’s most beautiful art. We may never know.

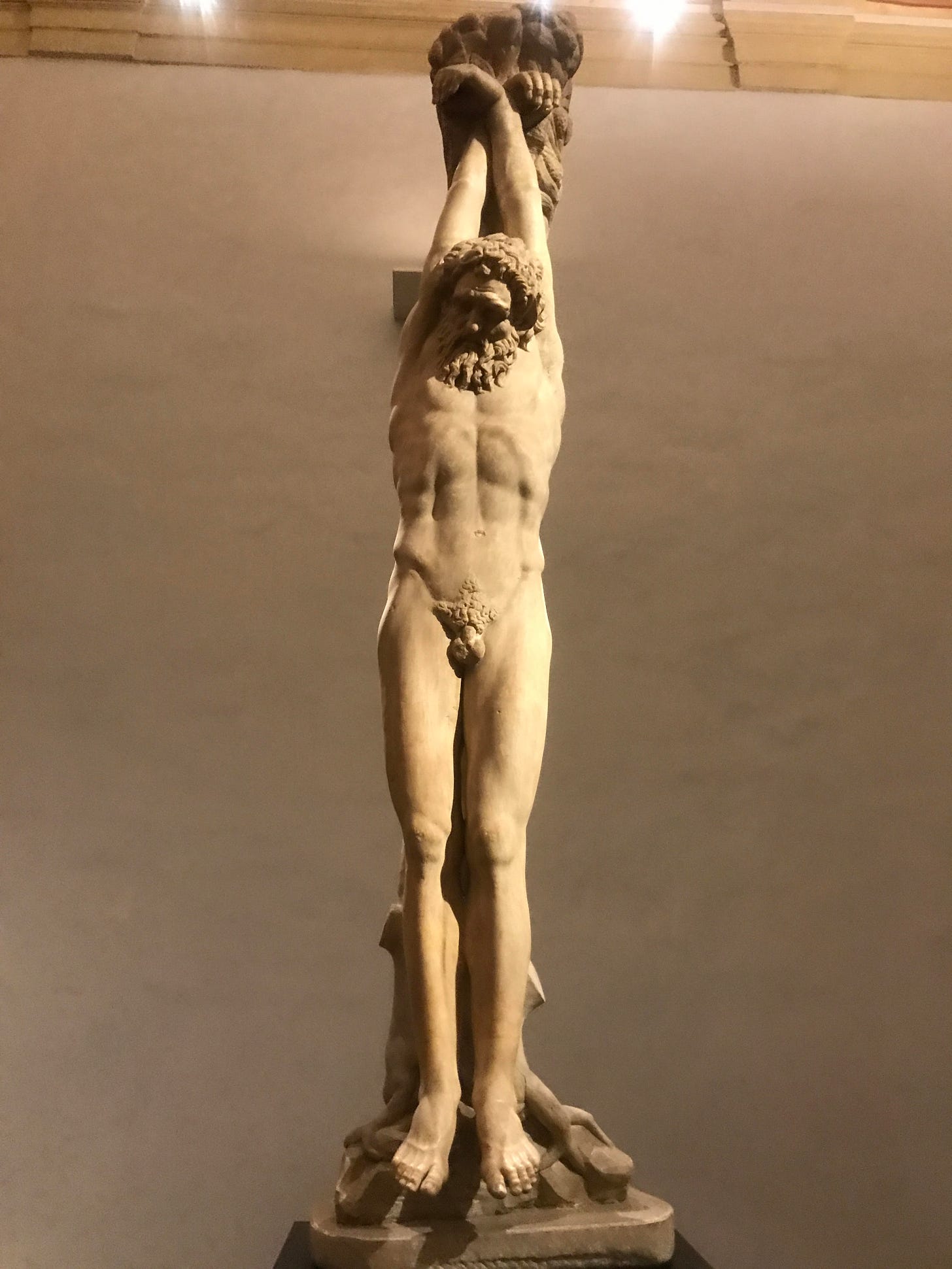

Anselm Kiefer’s exhibition ‘Fallen Angels’ in the Palazzo Strozzi, uses lashings of gold in giant paintings that cover whole walls. Not usually a fan of this kind of art, I found it fascinating due to its mythic dimension, and the Palozzo was at least a bit less crowded than the Uffizi.

Engelssturz is inspired by the fight between the archangel Michael and the rebel angels described in the Book of Revelation.

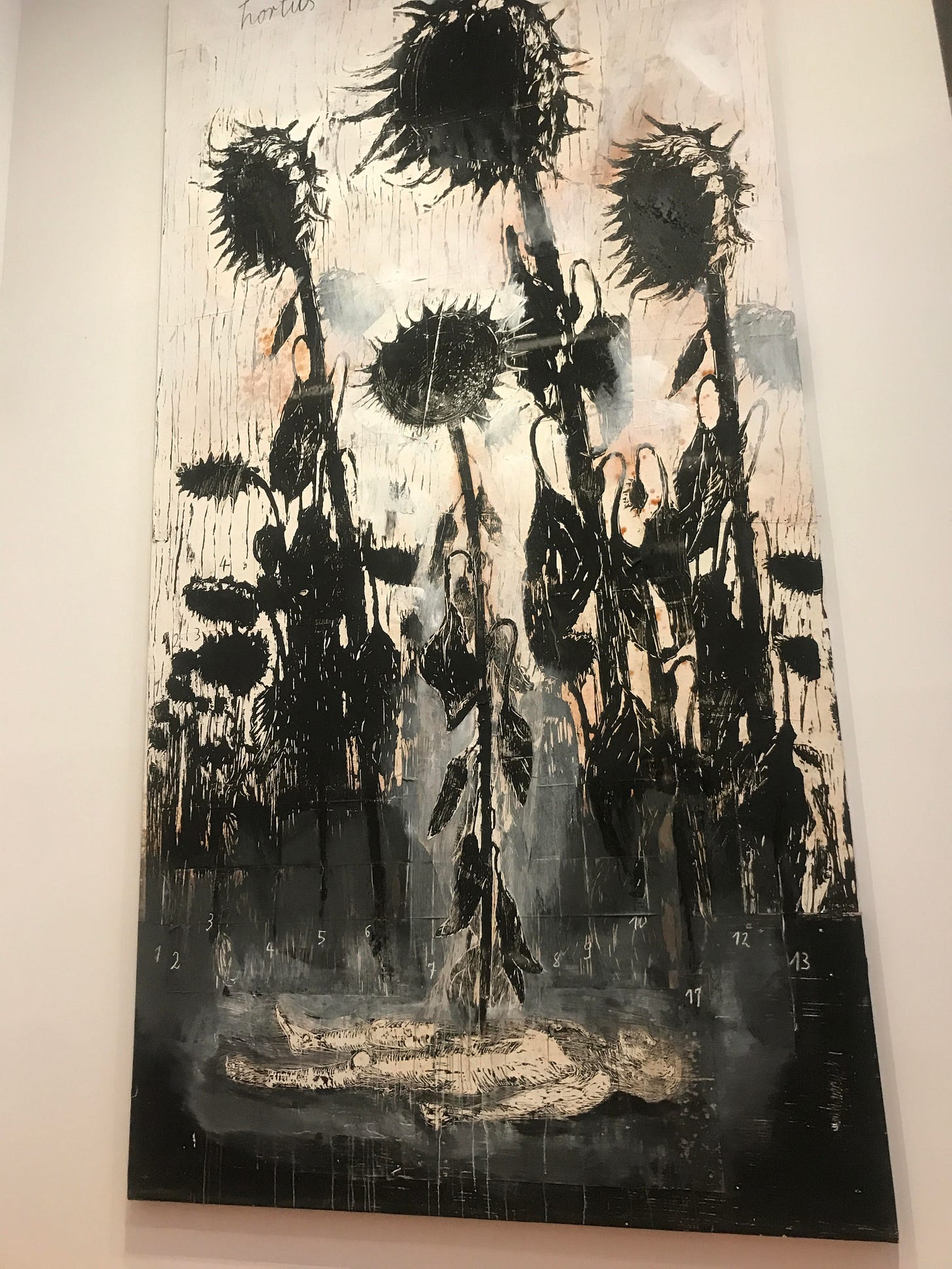

Then there is the room of Sunflowers, a tribute to the French avant-garde artist, actor and dramaturgist Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) and his novel Héliogabale ou l’anarchiste couronné (Heliogabalus or the crowned anarchist, 1934).

The novel is a biography of 3rd century Roman Emperor Heliogabalus, a potent mix of sexual excess and decadence, self-deification, violence and reflections on the occult, and Satanism. Obviously, Artaud’s depiction of the Emperor's reign is subjective and surrealist, a phantasmagoria with remnants of the sun-god religion.

“An incendiary work that reveals both the divine cruelty of the Roman Emperor and that of Artaud himself.” - Stephen Barber

I’m very fond of Artaud, inventer of the Theatre of Cruelty, who, some say, had his own pet lobster that he walked around Paris on a lead. We do know that Artaud arrived in Ireland in 1937 with what he claimed to be St Patrick’s staff. To him, this was a spiritual mission of sorts, and the staff possessed magical qualities. Along with the staff, he carried a letter of introduction from the Irish Legation in Paris, who were unaware of the nature of his pilgrimage. He would end up in Mountjoy Prison for his troubles, before being deported as a “destitute and undesirable alien.” Read more here.

During his rule, the Roman emperor Heliogabalus introduced the worship of the Sol Invictus (invincible Sun) as an alternative to the Latin god Jupiter. His brief existence, cut short by a conspiracy at the age of nineteen, embodies the precariousness of power. Sunflowers symbolise our own photosynthethic tendencies as humans, to strive towards light. Especially in dark times, as we have now. Kiefer says “Painting nature in isolation isn’t feasible; it must be understood in the context of historical events, such as wars.”

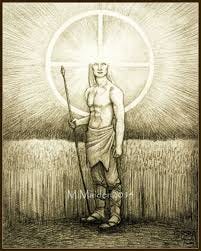

Sol Invictus is the Invincible Sun, or Unconquered Sun, the God of the late Roman Empire. Emperors portrayed sol invictus on their official coinage, claiming the "Unconquered Sun" as a companion to the Emperor, which Constantine used. Sol Invictus appears on the Arch of Constantine.

Might not be a bad idea to invoke the Unconquered Sun, in Ériu, before we wither. Lugh is our own god of the Sun and Light.

So beautifully human, ethereal yet also so direct, a commentary without comment, yet powerful statement nonetheless.

It is perhaps at this point where I'm supposed to share and compare my own experiences, in order to build connection. All I can say concerning this great art, is that the honouring of pagan ways which were sacrificed on the altar of ghoulish pain seemed to carry even then a beauty and an association with finer realms than this one.

There is a heaviness and a darkness to the Christian works, as in Kiefer, that only pretends to greater things. It is fitting that this is so, for after the church completed its appropriation of the sun and the moon, it quickly forgot about them, and the luminaries became dead things, in a dead universe, under a dead sky.

I would hope that those who could afford it would more than buy you a coffee, Siofra. Your writing has a delecate beauty that is exceedingly rare in this world of hard edges.

Thanks.

I love everything about this piece Síofra and most especially, how you make it seem effortlessly stream of consciousness, when I know so much work goes in to achieving that. The quirky humour is unmistakably you and so enjoyable to read 🥰